There’s a big company in Sacramento that provides services everyone needs but tries to avoid. The pandemic wrecked the company’s business plans but made it more essential than ever. And the company is in trouble with the state attorney general.

The company is Sutter Health.

These are difficult times for Sutter, which began 99 years ago as a private hospital to replace an adobe clinic near the corner of 28th and K streets. The motivation for Sutter was the 1918 flu pandemic, which killed almost 30,000 people in California between 1918 and 1921—when the state had just 3.5 million residents.

Threatened by the virus’ efficiency, medical and civic leaders were eager to build a modern hospital. They named it after the fort across the street.

Today, Sutter is anything but a lone hospital. It employs more than 53,000 people across a network of five regional medical foundations and 24 hospitals in Northern California and Hawaii.

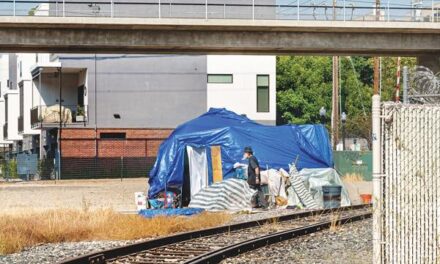

Despite its size and success, Sutter faces unprecedented challenges. The COVID-19 crisis disrupted deliveries of medical services and prompted people to delay or skip doctor’s visits. Critical-care beds have filled with coronavirus patients. Simple acts such as visiting loved ones at Sutter Medical Center are either impossible or extraordinarily hard.

And Sutter Health is trying to manage a $575 million settlement with State Attorney General Xavier Becerra, who accused the nonprofit of price gouging and monopolistic behavior. Unions and employers joined the lawsuit against Sutter.

Sutter Health is doing its best to soldier on, as illustrated by a statement to Inside Sacramento from Dr. William Isenberg, chief quality and safety officer: “Our hospitals, clinics and all care facilities are open and ready to provide care. We’ve taken several steps to help our patients, clinicians and staff remain safe.”

Isenberg says Sutter mandates masks and isolation wards for patients with COVID-19 symptoms. He mentions screenings for all employees when they start their shifts. He cites extra cleaning and disinfecting procedures.

For Sutter Health, the narrative goal is to make the community believe things are as normal as can be. The Sutter website opens with a headline proclaiming, “It’s time to get the care you’ve been waiting for.” A subhead addresses anxieties: “We’re taking extra precautions to keep you safe.” A blue COVID-19 banner shows pandemic resources, but once the banner is closed, coronavirus references all but vanish.

In his statement, Isenberg acknowledges various preparations for coronavirus surges. But the pandemic hasn’t stopped Sutter’s ability to perform routine duties. He writes, “We are experiencing an increase in cases in some of our footprint. Because of the breadth of our network, we are able to care for both COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 patients across our communities.”

Despite efforts to move forward, Sutter Health is financially hurting—thanks largely to the virus. The pandemic prompted Sutter to seek and receive hundreds of millions of dollars in federal aid. At the same time, Sutter tried to delay payment on the $575 million settlement.

The agreement followed a lawsuit where the attorney general claimed Sutter Health patients, their employers and unions were forced to pay inflated prices for medical care.

In trying to delay or renegotiate the settlement, Sutter downplayed its “open for business” narrative. The virus was prominent in Sutter’s defense—it’s why Sutter might seek to increase fees beyond limits established by the settlement.

“Adjusting our entire integrated network to respond to COVID-19 has been an incredibly costly and difficult endeavor that will significantly impact us for years to come,” Sutter says in a statement.

Add to these problems a symbolic dilemma. Sutter’s identity is being challenged by calls to rid the community of racist legacy monuments. In the 1800s at his fort, John Sutter enslaved hundreds of Miwok and Maidu people. He was responsible for the assaults and deaths of countless Native Americans.

As social justice protests moved through Sacramento this summer, Sutter Medical Center removed a statue of Sutter after it was vandalized with paint. The name stayed.

R.E. Graswich can be reached at regraswich@icloud.com. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram: @insidesacramento.