An Inside reader named Ken Poppers serves as today’s example of someone with a good memory. I’ll play the role of the old sportswriter who needs a reminder.

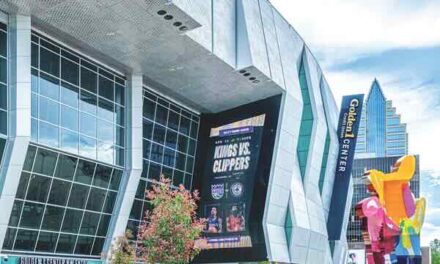

Poppers emailed me recently and noted my disdain for the Kings and their avoidance of certain fiscal responsibilities in the pandemic. When COVID-19 hit, the Kings cut staff. They also stopped paying all the rent they owe the city for Golden 1 Center.

From a strictly business standpoint, the Kings’ retrenchment is understandable. Home games and concerts were canceled, the arena shuttered by health authorities. Plenty of businesses have trouble paying rent these days.

Aside from cash flow denied the Kings by the absence of fans and activity in the arena, the NBA’s TV revenue-sharing model imploded. Shared TV dollars are oxygen for the Kings.

The NBA normally receives about $2.6 billion a year for broadcast rights from ESPN and Turner Sports. The money is spread among 30 teams. Some of that lifeline was salvaged when the NBA completed an abbreviated 2020 season in Florida. But financial analysts figured the league lost about $1.5 billion to COVID-19 in 2020.

The Kings returned to action just before Christmas, but the bottom line hasn’t exactly rebounded. The 2021 season was shortened by 10 games. Fans still aren’t filling Golden 1 Center. Tickets, beer and hamburgers go unsold. Cash registers are quiet.

In a world of COVID-19, these problems would be relatively insignificant if not for a discomforting reality. The Kings are a collection of wealthy owners and rich, pampered athletes. They should have the financial depth to sustain themselves. But they must not forget they have a working-class partner—the taxpayers of Sacramento.

When the Kings flail financially, the turbulence shakes the city’s budget. As owner of Golden 1 Center, the city is responsible for paying down the bonds that produced the money to build the arena. When the Kings skip on rent, bankers and bondholders shrug. They know the city is on the hook for about $18 million a year in debt service.

The Kings failed to pay about $1.6 million in rent last season. That number might double this year. In addition to rent, the city uses garage and street parking revenue to pay the bonds, plus money from parking citations. With hardly anyone parking Downtown, Sacramento lost about $3.2 million in fees during the early months of pandemic lockdowns. The shortfalls continue.

Luckily, City Treasurer John Colville and predecessor Russ Fehr had a fallback plan. When the arena bonds were issued in 2015, the city built a reserve in case parking revenues came up short. Colville tapped $4.5 million from those reserves to cover the bond payments. I’d like to talk to Colville about his plans for this year, but he hasn’t responded.

Which brings me back to Ken Poppers. In his email, Poppers mentions a November column where I discussed the Kings not paying rent. And Poppers reminds me that in 2014, I participated in a series of public policy debates over the arena. Back then I said the city had no choice but to help the Kings pay for Golden 1 Center.

“You debate on the side of committing the city to financing the arena because there couldn’t be any downside. Yeah. Okay,” he writes.

He’s mostly accurate. I said the city must help build Golden 1 Center. Without rejuvenation provided by the arena, lower K Street and Downtown Plaza would soon be blighted blocks of boarded-up shops. As for downsides, I said they existed but were worth the risk—the alternative was worse. I still believe that.

In upcoming years, the Kings’ rent payments grow significantly. Golden 1 Center bond obligations run until 2050. The partnership must endure.

Sports fans know it’s not easy to have faith in the Kings. But now is a great time for the community to remind the Kings that even NBA owners must pay their debts.

R.E. Graswich can be reached at regraswich@icloud.com. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram: @insidesacramento.