Generations of families loved Land Park Plunge and Riverside Baths. They celebrated the pool’s opening every April, rode bikes, walked or took the No. 2 bus down Riverside Boulevard.

They splashed in “artesian” waters on summer days. They swam on moonlit nights. Admission was 25 cents, kids a dime.

Then Land Park Plunge and its diving boards, patios and dressing rooms disappeared, dropped from conversations, expunged from memories, an embarrassment best forgotten.

Today nothing memorializes the significance of a once-grand community sports and recreation center. Let’s pretend this never happened. But it did happen.

There was a problem with Land Park Plunge and Riverside Baths. The park was proudly, openly segregated. Black families were turned away. You can’t swim here.

If there was a more prominent and beloved racist Sacramento public facility, I’m unaware of it.

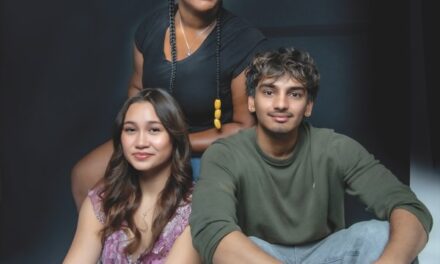

Racist policies didn’t stop Land Park Plunge and Riverside Baths from a half-century of success. Neighbors knew the rules and accepted them until July 1955, when the pool abruptly closed, citing maintenance problems.

The owners never hid their bigotry. They boasted about it. Capitalized on it.

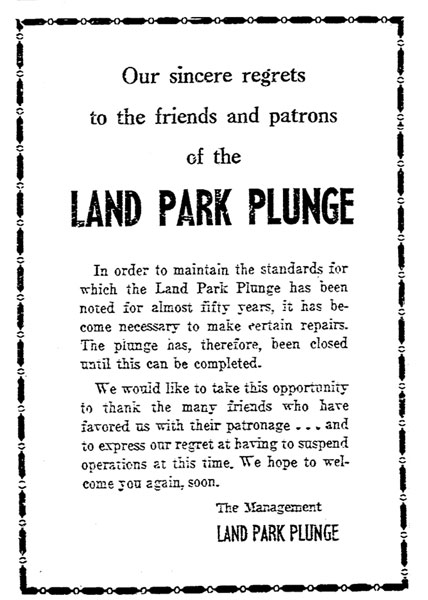

Throughout the 1940s and early 1950s, the pool published newspaper ads saying, “We reserve right of admission” and “Exclusive! Some not admitted” and “Whom to admit reserved.”

Racial codes were enforced from 1909, when Riverside Baths opened. In 1921, Lillian Kana, 13, was barred after attendants decided she was Black. Lillian was Hawaiian. Didn’t matter. Pool manager Walter Dyreborg explained:

“The fact is that we must maintain a high standard of trade in our baths and so must exclude all of a dark race. Of course, by law we cannot refuse admittance to anyone because of color, but we can say to the Chinese, Japanese, Hindu or Negro when they apply for admission that it will cost them $100 to swim in the baths. Public spirit is back of us in this respect.”

Dyreborg was right about public support. Bigotry prevailed for another 30 years. Restrictions at Land Park Plunge and Riverside Baths gave white families an excuse to patronize a racist business because the owners were honest, important men.

They announced their policy up front. They claimed their freedom to select their customers, a proprietor’s “right of admission.”

A 14-year-old girl named Hazel Jackson broke the barriers at Land Park Plunge. Young Hazel showed Sacramento how the “right of admission” belonged to her, not racist pool owners and neighbors.

On May 23, 1952, Hazel’s class from California Junior High School traveled 10 blocks from campus to the plunge for a picnic. Pool employees stopped Hazel. She was Black. No Black people allowed.

Hazel’s grandmother, Hattie Jackson, contacted Nathaniel Colley, the city’s lone African American lawyer. Colley filed a $10,000 damage suit against the pool three weeks later.

On July 15, Judge J.O. Moncur approved a $250 settlement for Hazel, plus attorney’s fees. The deal applied only to Hazel, not other victims of discrimination.

But anyone who knew Colley realized he would sue every time the pool denied entry to a Black person. Hazel shattered generations of Land Park racism.

The Riverside pool was more than a sports and recreation facility. It was a community center, created as a public benefit corporation.

Prominent citizens financed the pool and policies. Among them were John T. Greene, a lawyer who built grand homes along H Street, and real estate millionaire David Wasserman.

The indoor Riverside Baths were torn down in 1937, replaced by a 121-foot outdoor pool. The name was changed to Land Park Plunge in 1947.

Ownership shifted but always included local boldfaced names. There was baseball historian Vince Stanich, saloonkeeper Wayne Casey and Sam Gordon, founder of Sam’s Hoff Brau. All are dead, their racial opinions buried with them.

Hazel Jackson wasn’t prominent. Her bravery is forgotten. Hazel went to McClatchy High School, moved to Philadelphia and became a key punch operator. At age 31, she committed suicide.

Sam Gordon sold the pool property in 1958 to Congregation B’nai Israel. Price was $65,000. History not included.

R.E. Graswich can be reached at regraswich@icloud.com. Follow us on Facebook and Instagram: @insidesacramento.gram: @insidesacramento.