My husband and I live two blocks from the American River Parkway. Dog walks are daily events along dirt paths lined with old oaks and thick sagebrush. The river flows steps away.

We share space with snowy egrets, pond turtles, mallard ducks and Canada geese. Occasionally a family of mule deer allows us to pass.

The problem with having a majestic river in your backyard?

Sacramento is one of the most at-risk areas for flooding in the United States, reports the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

“After Katrina, the Corps took a hard look at the most at-risk cities in the country and started developing plans,” says Pete Spaulding, whose house backs up to the American River levee. The result included a 2016 flood-risk management plan to implement erosion control and bank protection along the Sacramento and American rivers.

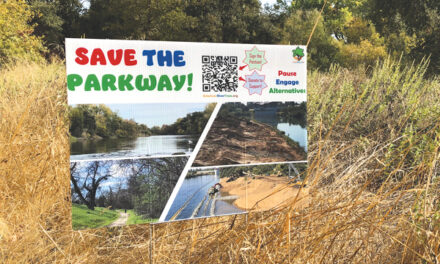

The Army Corps erosion-control project means “massive damage” to the American River Parkway and wildlife habitat, according to American River Trees, a citizens group calling on the Corps to reconsider its plans.

For a better idea of what might be in store, drive across the H Street bridge and look down at work completed already. Riverbanks near Sac State and Campus Commons, once verdant and lush, are barren. Destruction extends to Paradise Beach in River Park.

Next up are several miles along the lower American River from the Howe Avenue bridge to east of Watt Avenue. Established vegetation and as many as 500 trees, including 300-year-old heritage oaks, are scheduled for removal.

“Everybody sees what it looks like now by Campus Commons and Paradise Beach,” Spaulding says. “That’s what has encouraged us to speak up.” The Larchmont/La Riviera resident cites more than 900 letters submitted to the Army Corps.

Organizations speaking out include the Environmental Council of Sacramento, Save the American River Association, Sierra Club Sacramento, Environmental Protection Agency, National Parks Service and Bureau of Land Management.

Sacramento River Trees is calling for a more targeted, less destructive approach using new models and engineering approaches.

“There’s a whole push, not only within the Corps but the federal government, about Engineering with Nature,” Spaulding says. “Let’s use nature-based solutions to solve problems.”

The Army Corps touts Engineering with Nature in a December 2022 memorandum. The Corps “is committed to integrating EWN into our guidance and processes to facilitate the meaningful inclusion of natural and nature-based features into our projects.”

The Corps is “saying we need to use Engineering with Nature, not just for projects we’re going to do, but projects we’ve already started,” says resident Alicia Eastvold, who can walk onto the levee from her backyard.

“It’s about natural methods that preserve the ecosystem.”

Riprap (human-placed rock and rubble used to protect shorelines) is part of the current design. Eastvold wonders why the Corps doesn’t consider nature-based alternatives, such as logs and other woody materials.

Eastvold cites a Sonoma County project as an example of Engineering with Nature. “They kept the trees. They had meetings with the community. By the time they were done, it was a tourist attraction instead of a blight.”

Engineering with Nature calls for community engagement.

“It should be all about communication with the public,” Eastvold says. “We asked them (Army Corps) to come meet with us. Walk with us. You can show us and we can show you.” No response from the Army Corp.

“Every river is going to be different based upon the flow velocity, slope, gradient, vegetation,” says Spaulding, who has a degree in civil engineering. “We have to prevent the flooding, but let’s do it in a smarter way. Let’s use the most up-to-date models, data and techniques that we have rather than a one-size-fits-all.”

For example, advanced 3-D models of river flow show low velocities along the American River, even when waters are high, he says.

American River Trees asks, Why is the Corps taking such drastic measures in an area where erosion is minimal, seepage is not a problem and recreational use is significant?

Why hasn’t the Corps considered advanced research that shows tree roots protect against erosion, as well as maintain habitats for wildlife?

“All the animals will be gone—beavers, otters, bald eagles,” Eastvold says. “We are not saying, ‘No way.’ We’re saying, ‘There’s a better way.’”

Spaulding adds, “If the Corps would work with the community, we could have a project to be proud of for generations instead of a project that’s going to take generations to recover.”

The Army Corps did not respond to questions before this edition’s deadline.

Cathryn Rakich can be reached at crakich@surewest.net. Follow us on Facebook and Instagram: @insidesacramento.