A new public toilet in San Francisco made news with its first flush. The story wasn’t about plumbing. It was about adventures in bureaucracy.

Thanks to a bird’s nest of bids, permits, reviews and inspections, the toilet required two years and a budget of $1.7 million.

Authorities later said the price was closer to $200,000. But the point was made. Cities fumble simple, basic projects.

Sacramento has a simple, basic project that makes San Francisco look speedy—a bike path 108 years in the making.

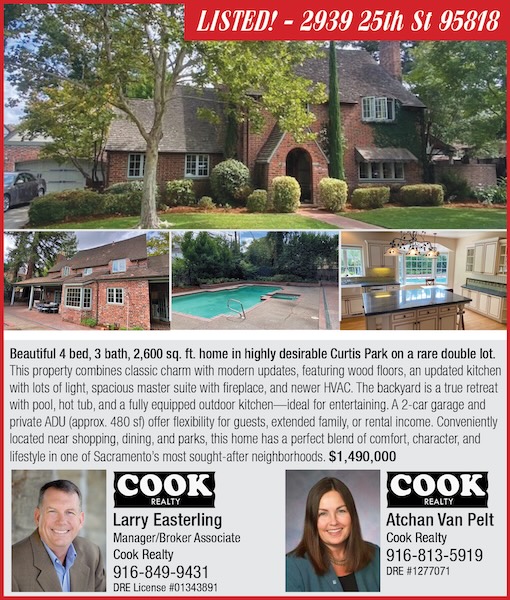

Noah Painter, partner at KMP Strategies; Megan Johnson, senior engineer with the city of Sacramento’s Public Works; and Tim Chamberlain, principal environmental planner with Wood Rodgers on the levee at Garcia Bend Park.

Photo by Aniko Kiezel

In 1975, city officials envisioned a bike path along the Sacramento River levee from Pocket to Downtown. The project revived a 1916 parkway laid out by John Nolen.

Passing through Sutterville to Miller Park, the paved path will connect with the American River Parkway bike trail. It’s a regional treasure for diverse neighborhoods, residents and visitors.

Today the community awaits its bike path, a century after Nolen drew his map, almost 50 years since the trail joined the city’s master plan.

Sacramento is ready to fulfill its promise with a 4-mile levee path from Zacharias Park to Garcia Bend Park. Funding is secure, plans are drawn, environmental reviews are wrapping up. Right-of-way acquisition and permits from state and federal agencies come next.

I talked to two civil engineers who lead the city’s levee trail project. I asked if everything is on schedule. The answer: yes. Completion is targeted for 2026.

I asked if the levee path is difficult from environmental review, permitting and construction perspectives.

The question almost made Megan Johnson and Matthew Salveson laugh.

There’s nothing complicated about building a bike path on the levee. Bureaucratic hurdles exist, but the river trail is far more streamlined than San Francisco’s toilet.

Delays to the levee trail are human obstacles, created by people who live nearby and disapprove of the bike path. Those same residents can help with solutions.

“Engineering wise, this is a really easy project,” Johnson says. “For me, the significance is really meaningful. We love our rivers. The ability to work on something like this is really cool. But there are combustibles that are very formidable to work through, with lots of conflicting needs.”

Salveson mentions his Ph.D. in civil engineering and says “it hasn’t been taxed” by the project. He adds, “This is about the community. It’s about people’s lives.”

Johnson says, “I have no doubt we can push through the process.”

The Central Valley Flood Protection Board, which owns the levee, agrees. Flood board Executive Officer Chris Lief says, “We stand ready to work with the city on their permit needs for this project.”

The levee bike trail faces no significant engineering or environmental challenges. Money isn’t a problem. But trouble lingers.

The challenge has always been a handful of property owners near the levee in Pocket and Little Pocket—people determined to slow or derail the project and stop cyclists and pedestrians from enjoying the river.

These residents regard sections of the levee as private property—their private park—and oppose efforts to finish the trail.

The property owners are organized, resourceful and persistent. The latest generation, led by wine merchant Ryan Bogle and SEIU researcher Mark Portuondo, advised by attorney Brian Manning, convinced flood officials to allow several temporary fences to block public access on the Pocket levee. The residents say the bike path will imperil their safety.

The temporary fence authorizations appear to violate the California Code of Regulations, state law that governs levees and other matters. Lief says the fences are “minor alterations” and thus legal.

Bogle, Portuondo and Manning are relative newcomers to levee bike trail battles. Their strategies date back decades.

Property owners in Pocket and Little Pocket sought fences in the early 1970s. They claimed their safety depended on keeping neighbors off the levee. Police data tell another story. Fences have no impact on police service calls.

John Nolen could have predicted that in 1916.

R.E. Graswich can be reached at regraswich@icloud.com. Follow us on Facebook and Instagram: @insidesacramento.