Show me a city that doesn’t demolish old buildings, and I’ll show you a graveyard. Progress cries out for rubble and rebirth.

This summer, the old Sacramento Bee headquarters at 21st and Q streets joined the roster of demolished landmarks. Wreckage never rests in a city hungry for growth.

Despite protests and lawsuits, the decrepit annex to the State Capitol was torn down in 2023. East Sac elders still dream about the Alhambra Theatre and its Moorish pillars and fountains, pulverized in 1973, replaced by a supermarket.

The Bee building began its slide into obsolescence 15 years ago when the newspaper’s influence and readership evaporated.

Once a citadel of the public’s right to know with a circulation of more than 300,000, the Bee and its fortress ceased to matter when the public moved online and stopped subscribing to the paper.

A half-dozen Caterpillar and Volvo crawling excavators knocked down the pressrooms and loading docks near 23rd Street. The machines chomped and scraped westward to the newsroom, cafeteria, library, doctor’s and business offices.

Soon the 1951 Streamline Moderne former headquarters of McClatchy newspapers were a pile of twisted rebar, broken concrete and shattered bricks.

I have no clue what it’s like to run a crawling excavator and destroy a building. I wonder whether demolition crews are susceptible to post-traumatic stress and eligible for counseling.

I know colleagues from my time at the Bee—I spent 35 years in the newsroom—who wept over the dismemberment. It was home, symbolic of our labor and values. Those tears were really for us, not the building.

Not counting the destruction at 2100 Q St., the city likes to save old buildings. Historic sensitivities blossomed in the early 1970s when Sacramento created a preservation program to protect culturally significant landmarks.

A 1972 state law called the Mills Act gives tax breaks to people who sink money into historic structures. City Hall offers a website where residents can type an address and see if a building is historically relevant or worth fixing.

Historic City Hall, built in 1908, sets a good example. The landmark clocktower, offices and meeting chambers were restored in 2005. Behind the old building rose a new administrative center, curving around the relic in a bow to the city’s past.

Some towns would have demolished the 1908 structure and expanded its bootprint for a glass and steel monument to bureaucracy run amok. Not Sacramento, which honors history at Ninth and I streets. Or Eye Street as newspapers called it.

There are more good examples. City Council’s decisions to save and restore Memorial Auditorium and the Southern Pacific train station show a commitment to preservation, damn the expense. Both halls arrived in 1926, a proud year for Sacramento. Today those buildings are treasures.

Let’s measure the psychic cost of demolition. Consider the loss of legacy and historical connection. When old pillars and fountains tumble, dreams disappear. But before nostalgia settles in, weigh the value of what rises from the dust.

Maybe the Alhambra Theatre could have survived another 50 years as a movie palace. Who knows? The Tower Theatre, opened in 1938, chopped itself into three auditoriums and became a successful art house, circa 2025. The 1912 Crest succeeds now as a movie theater and event site.

The harder question is which iteration provides better value to today’s community, a lovely Moorish theater or a supermarket and parking lot?

In 1964, Edmonds Field baseball park at Broadway and Riverside Boulevard disappeared. The site became a Gemco membership department store. Today it’s a Target with theft issues. Does anyone miss foul balls on Broadway?

The land where the Bee stood for 74 years was Buffalo Brewery before the McClatchy family took over. Imagine the howls when the bottling lines fell silent.

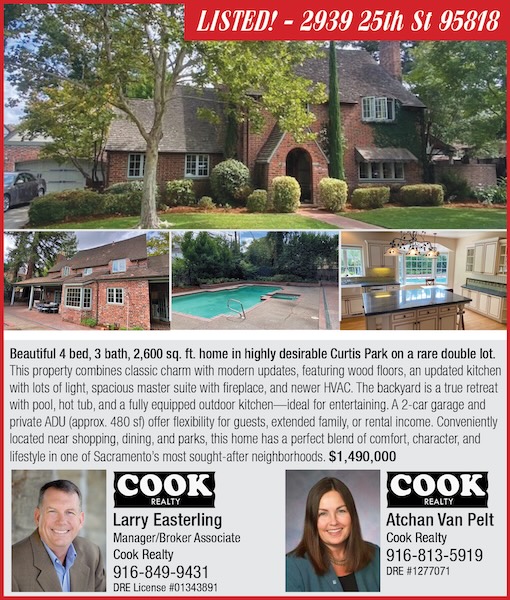

Next up for 2100 Q are 61 townhomes and 60 single-family homes. More valuable than a newspaper? Dumb question, circa 2025.

R.E. Graswich can be reached at regraswich@icloud.com. Follow us on Facebook and Instagram: @insidesacramento.