Dirty cops always lie. They know lying is an automatic way to get fired, but they lie anyway. This is where retired Sacramento Police Capt. Kevin Johnson comes in.

Johnson, who runs a business called Command Strategies Consulting, works for police departments across California. He breaks down the blue wall of silence and catches lying cops.

“If it looks like they are going to lose their job, people are going to lie,” Johnson says. “If we catch you in a lie, we fire you. My job is to overcome the wall of silence. It’s gotten better, but it’s still there.”

Police hire Johnson when they have serious disciplinary accusations that can lead to termination or long suspensions. He deals with racism, brutality, theft and sex. Fire departments hire him, too.

In a painful reality for many victims, it’s not easy to fire a cop or firefighter in California. They have special protections granted by a state law called the Public Safety Officers Procedural Bill of Rights, backed up by labor unions. And there’s the wall of silence.

The safety bill of rights intimidates many police chiefs, city managers, mayors and city council members. They think it’s a shield to protect dirty cops. I called Johnson to see if that’s true—he ran internal affairs for Sac PD and has written two books on dealing with problem cops. He’s seen many disgraced officers turn in their badges.

“The bill of rights is nothing to fear,” he says. “You just have to jump over some hurdles. One thing is, they have the right to representation. That’s fine. It doesn’t stop me from getting to the truth.”

Police chiefs cause problems by needlessly expanding the bill of rights. While an accused cop can have a lawyer or union representative when interrogated by Johnson, a cop who may have witnessed the offense has no such rights. But many chiefs let witness officers have a rep anyway. The reps become transmission belts—telling the accused what other witnesses said. Miraculously, everyone’s story lines up.

“Why they do that is beyond me,” Johnson says of police chiefs. “It hinders the integrity of the investigation.”

There’s a reason why chiefs extend the bill of rights to witnesses—politics. They don’t want trouble from unions. They don’t want pressure from the city manager, mayor or city council members. They don’t want to face a vote of confidence.

“Chiefs shoot themselves in the foot when they do that,” Johnson says. “It’s done to appease the union.”

Cops who are simply witnesses don’t need a rep because they aren’t under investigation. If a witness cop implicates himself, Johnson ends the interview. The confession can’t be used.

Another mistake police leaders make is they quickly inform a cop when he’s under investigation. Johnson wishes they would keep it quiet for a while. Police generally have one year to investigate complaints. “I can follow them around, watch them and not let them know I’m investigating them,” Johnson says. “When a chief tells them immediately, it stops the behavior.”

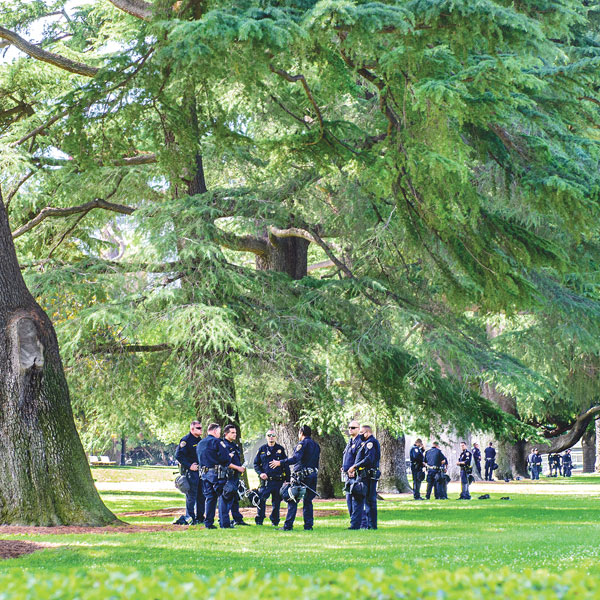

Investigation methods are timeless. Talk to the person who made the complaint. Visit the scene. Review videos, including in-car, body and security cams. Follow the accused. Interview witnesses. Interrogate the accused.

“You can’t refuse to answer,” Johnson says. “That’s insubordination, and that means termination. I can’t hit you with a phone book or swear at you, but you have to answer my questions. That pisses off a lot of people.”

Many brutality cases involve older officers. They resort to brutality because they are scared, Johnson says. They have forgotten their training. “Rookies have just spent months in the academy working on control holds and leg sweeps,” Johnson says. “They are physically confident. If you haven’t been retrained for 10 years and get into a fight, you will resort to street fighting.”

Even when handled appropriately, arresting someone who doesn’t want to go never looks good. “It’s always ugly,” he says.

Johnson was a second-generation Sacramento police officer. He recalls a reform experiment from his dad’s era in the late 1960s when SPD patrol officers wore blue blazers to make them seem less intimidating. “People thought the cops had no authority,” he says. The blazers were quickly gone.

R.E. Graswich can be reached at regraswich@iclould.com. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram: @insidesacramento.