Dec 28, 2024

Cinnabon is a cinnamon-colored pit bull, all muscle with a tongue that dangles from a smile stretching the limits of her wide jawbones.

Okapi, a solid black German shepherd, has gigantic puppy paws that, at 4 years old, she has yet to grow into.

Tom is a senior—an 8-year-old mix of rottweiler, shepherd, perhaps a little pit bull.

All three dogs are gentle, calm and curious. They are ideal candidates to get out of the county animal shelter and walk a park trail, lounge on shaded grass, sneak favors on a restaurant patio—even for just one day.

Nov 28, 2024

The dog stood in front of a used tire shop in an industrial section of town. His gait was slow and weary over dirt and gravel. A cardboard box on a cement pad by the front door was his makeshift doghouse.

Filth gripped his ratty black and white fur. Twisted mats hung from his torso.

A passerby called 311 to report a loose dog in poor condition. A city animal control officer went out. He spoke to the dog’s owner and left—without the dog.

“We did go out and while it’s not the best setup for him, he does have access to the back area of the shop,” says Phillip Zimmerman, manager at the city’s Front Street Animal Shelter.

Nov 28, 2024

For more than a year, American River Parkway supporters have called for a redesign of erosion- control plans by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

The Army Corps intends to bulldoze through fragile river parkway landscape, destroy riparian habitat, replace shoreline with rock and rubble, and threaten countless wildlife to protect the city from floods. The project, called Contract 3B, runs from the Howe Avenue bridge to east of Watt Avenue.

But when a draft environmental impact report generated negative comments from the public and agencies—as many as 1,900 letters—the Army Corps postponed its work until 2026.

Oct 28, 2024

The green sturgeon is an ancient creature. This “river dinosaur” dates back 220 million years. Today he thrives in local waterways.

The southern green sturgeon spawns in a small segment of the Sacramento River and uses the lower American River for juvenile rearing.

Despite the green sturgeon’s resiliency, the species is listed as threatened under the federal Endangered Species Act.

Sep 28, 2024

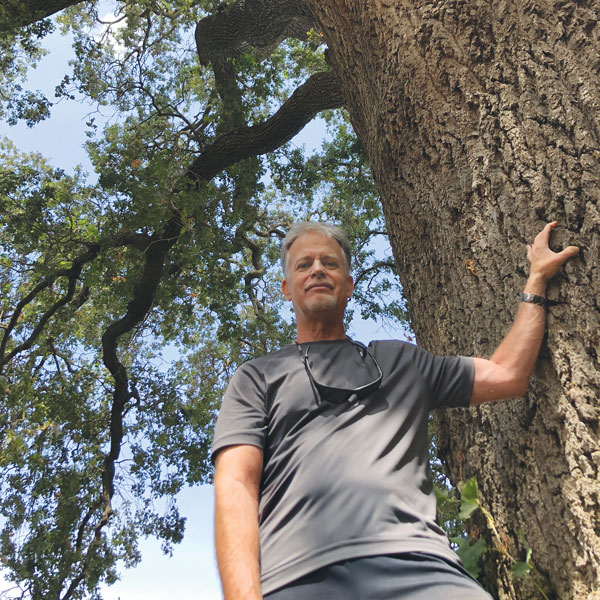

Heritage oaks have stood along the American River Parkway for more than 300 years.

Valley, blue and live oaks provide shade and shelter for wildlife. Tree canopies cool the river water, critical for spawning salmon and trout. Squirrels and birds rely on the acorns for food. People bike, hike and picnic under twisted branches.

If left to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, as many as 700 trees, including sycamore, alder, ash, cottonwood and 100-foot-tall heritage oaks, will topple.

Sep 28, 2024

It started in the Galapagos 20 years ago. The first spay/neuter clinic was on Isabela Island. The first patient was a dog named Luna.

Today, Animal Balance deploys high-volume temporary MASH clinics (Mobile Animal Sterilization Hospitals) in 10 countries, including the United States.

In March, Sacramento hosted its first three-day MASH in partnership with Sacramento County’s Bradshaw Animal Shelter, converting a county-owned building at McClellan Park into a spay/neuter hospital.