Dec 28, 2023

Coming from the colder mid-Atlantic region, I was amazed by the valley’s ability to produce citrus and other exotic fruits, such as pomegranate and persimmon.

Then I saw juicy tomatoes smashed near highway exits, lemons and oranges moldy underneath their trees, plums dyeing sidewalks purple. So much abundance, so much waste.

Matthew Ampersand and partner Tessa D’Arcangelew Ampersand experienced the same shock when they arrived in town and noticed food rotting in plain sight.

Nov 27, 2023

My dinner tonight is tender, flakey and buttery black cod, known as sablefish, drizzled with extra virgin olive oil, torn basil confetti and crushed cherry tomatoes.

It’s the freshest fish I’ve had in town—and it came from a waterfront stand off South River Road in West Sacramento.

Down South River Road’s bends and twists, across the river from Pocket and just before Vierra Farms, there’s sign for Ferrari Fisheries. The trail leads to a stall with a table and containers.

The sign brings to mind the timeless, muddy Sacramento River floating past. Yet here is some of the area’s freshest ocean fish. The fisherman is Anthony Ferrari. He carries on a family tradition started decades ago by his father.

Oct 28, 2023

One of the many aspects I love about Sacramento is how, in the middle of urban and suburban sprawl, we have pockets of agriculture—acres that reflect our agrarian roots. In this beautiful place, we are reminded of the connection to fertile soil and ideal growing conditions on almost every block.

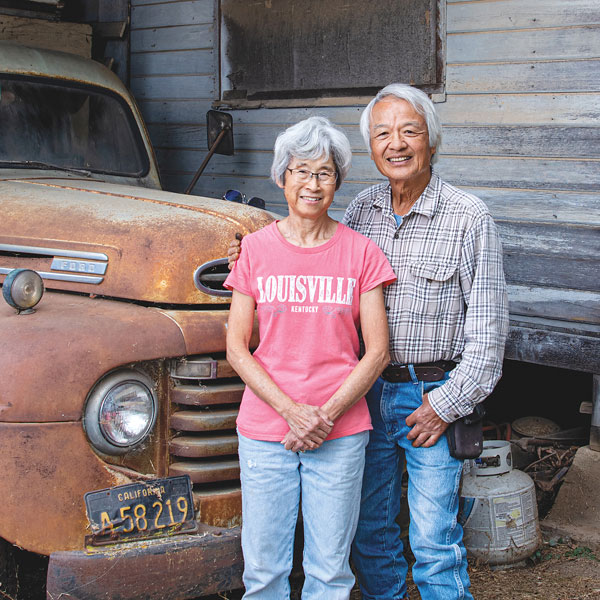

Otow Orchard in Granite Bay captures this convergence between a populous region and its steadfast agricultural lands. Minutes from Douglas Boulevard’s big box stores and shopping plazas rests an oasis of fruit trees tended by the Otow family since 1911.

Sep 28, 2023

Soil Born Farms is the farm in the farm-to-fork capital.

Walking the farm at American River Ranch, off Chase Drive in Rancho Cordova, the bounty and its possibilities present themselves in powerful ways.

First, let’s admire the farm beds, prepared a year or two in advance with cover crops that promote carbon sequestration. Next, here’s an area soon to be planted in tall oaks. Nearby is a restored creek, cleared for salmon and steelhead spawning.

A walkway features hundreds of California native plants. An outdoor classroom is shaded by hanging grape clusters. At the demonstration garden, children find runner beans, sunflowers, peppers and tomatoes flush for picking.

Aug 28, 2023

For almost six years, I cooked at a farm-to-table restaurant that bought a whole lamb every week, locally raised, sustainably grown.

We butchered down the lamb into meals and made salumi and sausage with the scraps. Bones went into our Brodo, a mixed meat stock. We cooked and sliced kidneys and tongues for salads or antipasti dishes. Every part of the lamb was used and appreciated.

I also worked for restaurants and catering companies that relied on industrial produced lamb cuts, racks and deboned legs, shipped from Australia or New Zealand, where the animals were brought to slaughter in mass for lower cost.

Jul 28, 2023

One afternoon in my community college English classroom, four students arrived with an assortment of Fiery Hot Cheetos, Skittles and sodas. Students aren’t supposed to eat in classrooms, but it was lunchtime. I knew the students were hungry and didn’t interrupt their snacking before class.

No surprise, by our 1:30 p.m. break, the students who devoured vending machine snacks were lethargic and barely able to participate.

The trends are horrifying and unmistakable. Forty percent of California fifth graders are overweight or obese. A disproportionate number among them are minority students. We know young brains need nourishment. The mind-body connection is under-addressed in our schools.

The Food Literacy Center wants to change how kids eat, teaching them about nutrition and how to prepare culturally relevant, nourishing foods.