Feb 26, 2020

Artist and humanitarian Marcy Friedman, Emigh Ace Hardware store owner Rich Lawrence and River City Brewing Company co-founder Beth Ayres-Biro will be top honorees at Carmichael’s 2020 Person of the Year gala. The event will be hosted by the Carmichael Chamber of Commerce at Arden Hills Athletic & Social Club on Friday, March 20.

Friedman will be honored as 2020 Person of the Year. Lawrence will be recognized as Businessman of the Year and Ayres-Biro as Businesswoman of the Year.

Feb 26, 2020

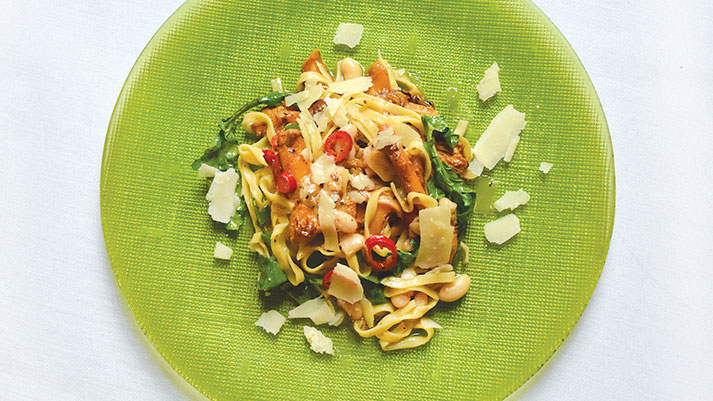

I’ve lived in Sacramento for almost 40 years, so I’ve been to Celestin’s Restaurant. It seems like a fact of life for any long-term diner in this town—if you’ve been around for more than two decades, you’ve eaten at Celestin’s.

You might have dined at the J Street location, where Patrick Celestin and his wife Phoebe held court starting in 1983. That same space became the first home of Kru Contemporary Japanese Cuisine, by the way. If my spatial geography is on point, I believe that same space is now the tiki bar extraordinaire, The Jungle Bird.

Jan 28, 2020

A prominent supporter of Measure G, the Sacramento Children’s Fund Act on the March 3 ballot, will pay state authorities $400,000 to settle a lawsuit for allegedly taking public money from migrant housing and spending it on restaurants, hotels, taxes and other personal expenses while overcharging farmworkers for rent.

Derrell and Tina Roberts, married co-founders of the Roberts Family Development Center of North Sacramento, quietly settled a lawsuit in August filed by State Attorney General Xavier Becerra. The settlement allows the Roberts to avoid a trial.

Jan 28, 2020

Katie Valenzuela saw people struggling to pay rent and buy groceries. She saw taxes going up. She heard promises from City Hall. But the promises were empty. And the problems got worse.

For solutions, she looked to her City Council member, Steve Hansen. She heard only excuses.

Jan 28, 2020

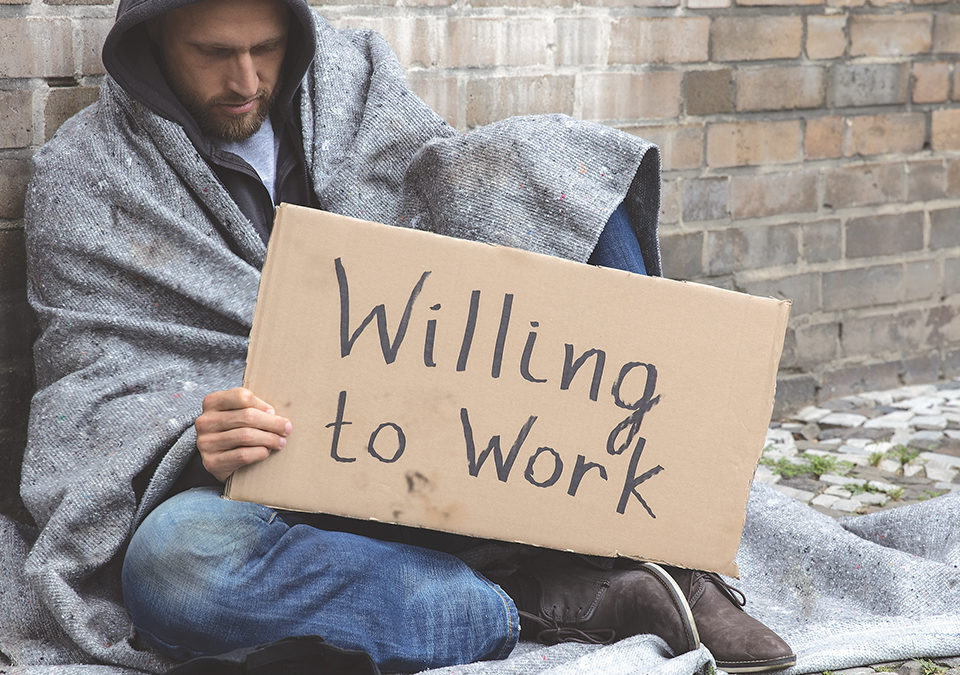

One of the most important questions I recall from childhood is, “What are you going to be when you grow up?” The question was not necessarily about jobs and pay. It was about life. Choosing a field of work defines who we are and how we live. It’s about what we accomplish and achieve.

The opposite of work is not leisure or play. It’s idleness. The philosopher Aristotle declared happiness resides in activity, both physical and mental. People who lack the joy of work—the feeling of a job well done—miss something important.

Jan 28, 2020

Think back to 2006. What do you think Sacramento saw itself as nearly a decade and a half ago? Where did you see Sacramento’s dining scene? Was farm-to-fork even on your radar?

In 2006, Heather Fargo sat as mayor, Kevin Martin led the kings in scoring and Patrick Mulvaney had a clear-eyed vision of what made the dining scene in Sacramento special. He recognized our rich agricultural legacy and year-round seasonal bounty, things we locals took for granted, as unique and something to be celebrated.