Pets and Their People

No More Bellas

This is about Bella and the system that failed her.

Dec. 4, a neighbor calls 311 about a dog at her apartment complex in South Natomas. The canine is left 24/7 on a small uncovered patio with no food or shelter. Storms are raging, temperatures are in the 30s.

Photos taken over the fence show a short-hair, medium-size, brown dog on a 3-by-5-foot cement patio. Her ribs protrude. She stands in her feces.

Stop The Breeding

More than 100,000 adoptable dogs and cats are killed in California animal shelters each year—second only to Texas.

California has made progress. In 1998, we destroyed a half million dogs and cats annually. That year, the Hayden Act established state policy that no adoptable or treatable dog or cat can be euthanized at an animal shelter.

The killing slowed, but didn’t stop. Breeding continues. Shelters are overwhelmed.

Recognizing that we’ve fallen short, Gov. Gavin Newsom allocated $50 million in the 2020-21 state budget to make California a “no-kill” state.

Rescue Reset

The downy-feathered bird was almost lifeless, alone in the grass with no mom in sight. A small nest rested in the branches of a crepe myrtle a few feet away.

He was younger than a fledging, who would have hopped and fluttered in an attempt to fly. With no protection, the chick would not survive a roaming cat or the afternoon heat.

I returned the youngster to his nest. After an hour of waiting and watching, no mom or dad returning to the scene, I placed the chick in a box and drove to Sacramento’s Wildlife Care Association.

Fixing Front Street

A dog with no microchip, no ID tag. A door left open or a hole in the fence. Someone willing to do the right thing—get the dog off the street.

Now what? Is taking the lost canine to a local animal shelter the best way to reunite him with his owner? Is that where he will be safe? Is that where his parents will look first?

Or is it better to hold onto the dog, place signs around the neighborhood, post photos on social media, walk door to door?

Phillip Zimmerman, manager of the city’s Front Street Animal Shelter, likes the second option. So much so that he has instituted a “managed intake” policy at Front Street.

Who Will Help?

My husband and I noticed something amiss when our 13-year-old chihuahua mix, Tammy, was uninterested in breakfast. She was moving slowly, not the perky wide-eyed pooch spinning in circles for a morning treat.

I called our veterinarian’s office, assuming it would be booked for the day but hoping staff could squeeze us in. They couldn’t.

I reached out to six other veterinary clinics near our home in Wilhaggin. Only one was accepting new patients, but the wait was three weeks.

Alfresco With Fido

Sacramentans love their dogs. With two municipal animal shelters, a state-of-the-art SPCA, 22 off-leash dog parks and dozens of mutt-friendly restaurants, Sacramento canines are living big.

California law authorizes food facilities to allow pet dogs in outdoor dining areas as long as the city or county does not pass an ordinance prohibiting the pooches, and restaurant owners do not object. There must be a separate outdoor entrance and dogs must remain on leash and off chairs.

Rambunctious Rascals

Highly adaptable and irresistibly adorable, raccoons abound in Sacramento. Mischievous, clever and cute, yes. But raccoons can quickly become nuisances when they take up room and board in your neighborhood.

Ask neighbors about raccoons and stories come tumbling out. Mike and Gail Johnson on 38th Street tell of raccoons using the cat door to access their home and finding their way to a jar of kibble in the kitchen. One unforgettable day, a raccoon followed by two kits charged Gail when she found herself between their exit and the food source. No more cat door.

My Only Sunshine

Dominic is first to greet me when I push open the wooden gate. At 4 months old, this wiry-haired kid goat is playful, curious and sugar-coated. He was found tied up behind a business in Sacramento and taken to the Front Street Animal Shelter before making his way to Only Sunshine Sanctuary in the rural outskirts of Elverta.

Vegetables, a 5-month-old Jersey cow, nudges my thigh, his soft brown head begging to be scratched. “He’s like a giant puppy dog who loves to be petted,” says Kristy Venrick-Mardon, founder of Only Sunshine Sanctuary.

Bird Watching

Nestled 40 feet high in the branches of a willow tree, the great horned owl scrutinizes her surroundings. Two chicks are barely visible within the confines of their twisted twig nest.

Despite her skyward proximity and camouflage feathers, the bird of prey comes into touchable view through a spotting scope. Her home, along with 200 other bird species, is the state-owned Yolo Bypass Wildlife Area.

Stretching 16,000 acres across both sides of the Yolo Causeway along I-80 between Sacramento and Davis, the nature refuge is managed by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife for flood control, animal and habitat protection, recreation and education.

Too Much To Ask

Current law makes it a crime for people to deprive their companion animals of “necessary sustenance, drink or shelter.” But the statute falls short of what that means.

Necessary sustenance could be a loaf of bread or a candy bar—anything to keep the pet alive. Drink could be a can of Coke. A metal cage, just large enough for the animal to stand up and turn around, is considered shelter.

Last October, I wrote about a pit bull in the backyard of a Sacramento home. She lived 24/7 in a 4-foot by 6-foot chain-link kennel on hardpan dirt with a filthy water bowl and feces scattered about.

Smart, Loyal, Energetic

Walk through the county’s animal shelter on Bradshaw Road. The high-ceiling entryway opens to a spacious roundabout surrounded with glass-walled condos, each holding one or two large dogs, many pit bulls and German shepherds, and their mixed counterparts.

Stroll through the back door to an open-air corridor. Large windows allow visitors to view groups of small dogs housed together. Chihuahua and chihuahua mixes run back and forth, yelping with excitement. Further down are hallways lined with kennels housing medium and large dogs. Again, pit bulls and German shepherds dominate.

A New Direction

I’ve been in Sacramento long enough to remember the old county animal shelter—when “pounds” existed simply to impound strays. The dilapidated, dungeon-like building was cramped and dingy—where unwanted dogs and cats went to die.

When the public’s attitude toward companion animals began to change, shelters across the country broadened their scope to promote spaying and neutering, encourage adoptions, and recruit donors and volunteers.

The Forgotten Ones

“We got her!” Penny Scott’s text came Dec. 7, just after 7 a.m.

A female German shepherd, thin and fearful, had been seen for at least six months along the American River Parkway near the Estates Drive access. By day, she roamed the neighborhood and adjacent river trails. At night, she slept in the backyard of a home that abuts the parkway, slipping through a gap in the fence and bedding down in overgrown brush.

Runners, walkers and cyclists left food, but no one could win her trust. Early last December, a neighbor put out a call on social media. I reached out to fellow rescuers in the area. The response was unanimous—call Penny Scott. In less than 24 hours, Scott trapped the wayward pooch.

To The Rescue

A post on Nextdoor caught my eye. A senior gentleman looking for canine companionship asked for suggestions on where to adopt an adult dog. Dozens of people responded, citing Sacramento’s two municipal animal shelters and no fewer than 12 nonprofit rescue groups from Auburn to the Bay Area.

There are as many as 50 dog, cat and breed-specific rescue organizations throughout Northern California, reports the Sacramento Area Animal Coalition

Here And Gone

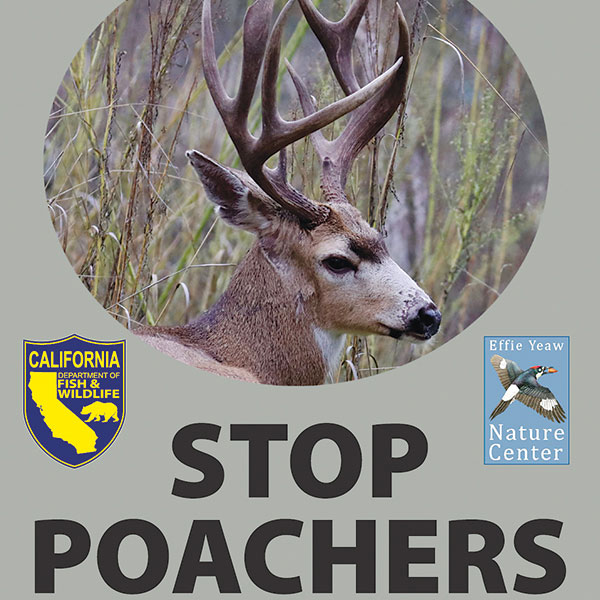

Their weapon is a crossbow—gunshots draw attention. They skulk under cover of darkness, late at night and early in the morning. Night-vision optics help locate their targets—big bucks with large antlers. The bigger, the better.

“They call the arrow a bolt,” says Tim McGinn, wildlife advocate, nature photographer and longtime member of the American River Natural History Association. “The tips are like five little razor blades. If they hit them in the lungs or chest area, the deer will last maybe two or three minutes. It’s lethal.”