Darrell Steinberg exposed his insecurities when he claimed credit for the latest homeless estimate.

The mayor’s performance was by turns narcissistic and self-defeating. His audience walked away confused.

The egomaniacal part was Steinberg’s insistence that his policies over the past eight years worked.

He boasted how the January 2024 homeless count revealed a 29% decline since 2022, dropping from almost 10,000 to 6,600.

The mayor insisted the decrease “is dramatic and affirms that the steady course we set seven years ago to address this state and national crisis is working.”

Ever deceptive, Steinberg failed to mention how the community had 2,700 homeless people when he took office in 2016.

The mayor neglected to reminisce how he built his 2016 campaign on a vow to eradicate rough sleeping on city streets.

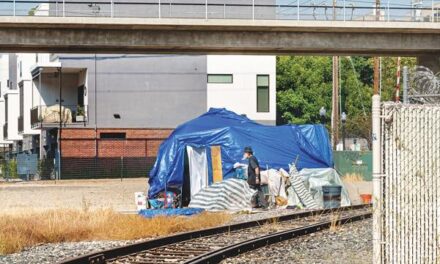

His plea to voters in 2016 featured an “I alone can fix it” melody. What followed were unprecedented years of sprawling tent communities, accompanied by crime, fires, open drug sales and general debauchery.

If starting with 2,700 homeless people and growing them into an army of 6,600 is success, I’d hate to see the mayor’s definition of failure.

Next came self-sabotage. Steinberg spoke too soon. Within minutes of his pompous victory declaration, the homeless count was under attack. The numbers look manipulated on the low side.

Squawks didn’t come from Steinberg’s political enemies. Skepticism came from homeless service providers and advocates—constituencies the mayor considers allies.

People who work the trenches of the homeless catastrophe are baffled by the new estimate.

They see none of the mayor’s rosy platitudes. They see an awful situation growing worse. They wonder if somebody messed with the data.

“It’s surprising, and frankly it’s absolutely unbelievable there’s been such a decrease in the community,” says Shannon Dominguez-Stevens, who runs a Loaves and Fishes shelter for women and children. “It doesn’t make sense.”

Ahh, but it starts to make sense with Steinberg in the frame.

The mayor is brilliant at backroom political machinations, talents he perfected during a climb through the state Legislature to the presidency of the state Senate.

Here’s a politician who feigned cluelessness when 10% of his Senate membership was hauled away in handcuffs for offenses major and small.

If there’s a way to fiddle with homeless estimates, Steinberg would know it. He maintains a blissful “who, me?” gaze of political innocence.

Politicians and media mistakenly treat the homeless count as a comprehensive census. In fact, it’s more like an unsteady game of pub darts. Key word in the report is “estimate.”

The count, which occurs over several January dates every two years (unless there’s a pandemic), is connected to federal demands and dollars. An exercise ripe for faults associated with subjective process and mandated urgency.

Counting zone definitions fluctuate. There’s the absurdity of hoping to tally individuals who don’t wish to be found and know how to lay low.

One variable is the reliance on 600 volunteer counters—missionaries with a list of 30 questions. Rain is a factor. And don’t forget homeless people are called transients for a reason. They move. If they aren’t where they are expected to be, they aren’t counted.

The count isn’t a real census. It’s a math problem. A snapshot, blurred at best. An exercise in random samples, statistical probabilities and calculated estimates.

Data-gathering is arranged by Sacramento Steps Forward, a nonprofit that serves as local clearinghouse for homeless services. I helped start Sac Steps Forward, but that’s another story.

For years, the headcount was conducted by Sacramento State University. This year, Sac Steps Forward replaced the Hornets with a San Diego outfit called Simtech Solutions Inc. That alone may explain the lower estimate.

The company guided the count and rendered the analytics. Sac Steps Forward insists it “double-checked, triple-checked” the methodology.

It’s no surprise homeless service providers and advocates are upset by shrunken numbers. Smaller counts mean fewer dollars.

Call it the irony of homelessness. Solving the problem would bankrupt nonprofits and throw their staffs out of work.

Steinberg will be out of work in December. Something the city can truly count on.

R.E. Graswich can be reached at regraswich@icloud.com. Follow us on Facebook and Instagram: @insidesacramento.