What a difference a pandemic makes. In spring 2019, a buoyant Mayor Darrell Steinberg, doing his best Daniel Burnham imitation to “make no little plans,” unveiled his big vision for Old Sacramento and Downtown.

Sacramento would leverage more than $40 million in hotel taxes left from the Convention Center and Community Center Theatre renovation and jazz up the waterfront. New attractions would include an outdoor concert venue, rooftop bars and a barge docked so people could swim safely near the Tower Bridge in our namesake river.

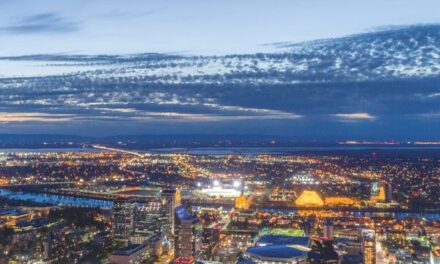

The central city had arrived. Downtown would finally get its must-see family attraction. Construction cranes were everywhere. The future looked bright. Steinberg would have a legacy other than heartache over the growing homeless and housing crises.

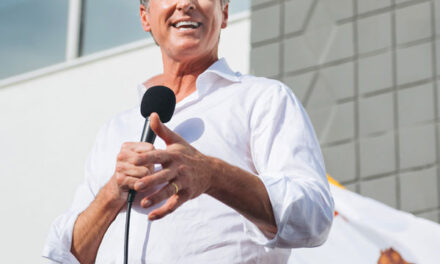

Two years into the pandemic, a still optimistic-sounding Steinberg told about 1,000 people at Downtown Sacramento Partnership’s annual State of Downtown breakfast in February what most of them already knew.

The waterfront makeover isn’t happening. All those state and other office workers fueling Downtown’s resurgence are not likely to return anytime soon.

“State, local and private sector workers have become accustomed to telecommuting—and they like it,” Steinberg told the audience. But as someone prone to turn lemons into lemonade, he added: “The reality poses either a threat or an opportunity, especially for mid-size and smaller office buildings.”

Owners of restaurants and other businesses that closed when office workers left might not want to hear it, but Steinberg sees opportunity where others see gloom.

For years, cities such as Sacramento advanced redevelopment projects through tax-increment financing. Bonds were sold based on expected tax growth in designated, often blighted areas. Millions of dollars were raised for various improvements. Over the decades, redevelopment’s record was mixed. There were notable successes, but plenty of waste and abuse.

After the state Legislature dissolved local redevelopment agencies in 2012, it created a new version two years later. The so-called “Enhanced Infrastructure Finance Districts” work similarly to redevelopment, but with more restrictions.

West Sacramento was the first California city to create such a district. As Steinberg noted, the city projects it can generate $535 million for infrastructure and affordable housing.

Steinberg now wants to convince his fellow City Council members to create one of these districts Downtown, floating bonds and leveraging capital to attract tens of millions of dollars more in state, federal and private funds for affordable housing, infrastructure and more of the mixed-used developments that give cities life around the clock.

As he says: “Simply put, it’s an economic incentive. It says to business, if you invest in our central city, we will return a percentage of the increase in property values to the central city. It can be bonded. It can be used for infrastructure, climate and affordable housing. It’s a potential game changer for our central city.”

Sacramento already has approved two such districts, one for the Downtown railyards and another for UC Davis Aggie Square off Stockton Boulevard.

As we look back over the last 24 months and take stock of the chaos, disappointment and uncertainty, it’s easy to feel worn down and worried about what’s next. Cities are no different. Lingering problems are exposed and grow worse. People are displaced. Good ideas blow away like smoke. It’s hard to feel secure and hopeful.

But crisis brings opportunity. If a tax-increment finance plan can get more people living and spending time Downtown, who knows? Maybe the pandemic leads to a healthier, more vibrant and diverse community.

This won’t pay off quickly. There are no guarantees. But like Steinberg, I feel better thinking it just might work.

Gary Delsohn can be reached at gdelsohn@gmail.com. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram: @insidesacramento