Robert Caro’s legendary book, “The Power Broker,” turned 50 this year and holds up remarkably well. The 4-pound tome about the notorious New York urban planner Robert Moses stared down from my bookshelf about half that long before I finally hauled it out and read it.

It takes commitment to open a 1,286-page book, which was even longer before Caro’s editor, Robert Gottlieb, trimmed 350,000 words. But it’s still a riveting read, now in its 74th printing and new digital version.

With concern in Sacramento over the dangers faced by pedestrians and bicyclists on local roads, this is a good time to read about a planner who championed the automobile.

Despite never holding elected office, Moses simultaneously held 12 appointed positions connected with parks, transportation and planning. He had no rival when it came to his impact on a large American city. Because of his unscrupulous use of power, mayors and governors bowed to Moses, not the other way around.

If Moses bowed to anything, it was the car.

Like a lot of city planners in his era—he reigned from the 1920s to the 1960s—Robert Moses loved projects that made life easier for cars and the roads they fill.

Interestingly, Caro’s book includes no mention of Jane Jacobs, the activist urban critic and legend in her own right who battled Moses over highways and pedestrian mobility.

Caro’s original manuscript included a chapter on battles between Jacobs and Moses, but those pages were cut. Jacobs had plenty to say about Moses elsewhere, including a letter to her mother quoted in the 2009 book “Wrestling With Moses,” which covers their conflicts.

“Well, we always knew Moses was an awful man, doing awful things, but even so this book is a shocking revelation,” Jacobs wrote to her mother about “The Power Broker.” “He was much worse than we had even imagined. I am beginning to think he was not quite sane. The things he did—the corruption, the brutality, the sheer seizure and misuse of power—make Watergate seem rather tame.”

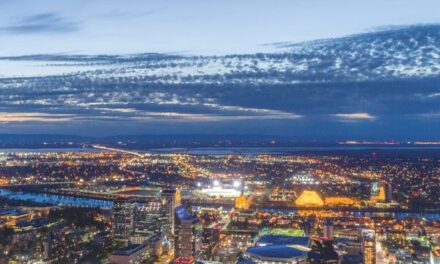

Moses’ approach to urban planning was replicated in many cities, Sacramento included. Building Interstate 5 to wall off the central city from the river is straight from the Moses playbook: Cars first, then everything else.

Separating Oak Park from the city with Highways 50 and 99 is another example of the Moses mentality.

Whether or not Moses was an evil genius, “The Power Broker” is a book for everyone who cares about cities and political power. Historian Sam Tanenhaus explains why in a New York Times piece.

“Its durability resembles that of Moses’ own prodigious creation, the redrawn arterial map of greater metropolitan New York,” Tanenhaus writes. “More than a dozen giant roadways girdling the city; seven bridges, their towers as tall as 70-story buildings; luxury high-rises, with color-splashed terraces and finials, placed at a remove from mile after mile of drab housing projects: prisons for the poor, especially the nonwhite poor, whom Moses did not want mixing—not on playgrounds and certainly not in swimming pools—with white people.”

What Tanenhaus doesn’t say is that by some estimates, Moses’ projects displaced more than a half-million people in the name of car access, vehicle convenience and urban progress.

Moses’ imperious style and ability to exercise and hold power seem anachronistic today. For all our political dysfunction, we are more Democratic now than during the 40 years Moses held sway in America’s largest city.

It’s hard to imagine anyone having a similar impact today. Just as it’s hard to imagine city planners in Sacramento worshiping the automobile now that we have so many examples of the damage they do to the urban landscape.

If you want a page-turning history lesson on urban America, it’s hard to beat “The Power Broker.” The book continues to captivate and enlighten readers with all the mistakes and missed opportunities it chronicles, 50 years after its debut.

Gary Delsohn can be reached at gdelsohn@gmail.com. Follow us on Facebook and Instagram: @insidesacramento.