Twenty-five years ago, my husband and I went into the local publishing business for two reasons. First, we saw the need to connect neighbors to one another, which helps folks build stronger ties to their communities.

Second, we love and value small businesses. We want to help local merchants reach their neighbors and grow their businesses.

When we moved to Sacramento in 1989, it took us five years to discover Corti Brothers market. An acquaintance raved about the gourmet landmark, saying, “Everybody knows about them!” That hurt—because we didn’t know. With the founding of our first Inside East Sacramento publication, I was determined to help neighbors like us find small businesses.

As an entrepreneur and new, small business owner, I soon met other people who struggled to learn the community. Many of those early connections are good friends today.

In the 1980s, two out of every 10 Americans worked for themselves. By 2016, that number fell to about one in 10. I suspect the percentage is lower in Sacramento, given the number of government workers. No doubt the percentage will shrink in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Small businesses are the backbone of our national economy. They employ more people than any other business sector. Locally, these establishments touch us every day. Their touch is physical, not just digital. And their ability to recover is in peril.

A study by the Society for Human Resource Management has tracked the impact of the contagion on work, workers and the workplace. The most alarming finding is 52 percent of U.S. small businesses expect to permanently shut down within six months because of mandated closures. This represents 14 million jobs erased. Even in good times, up to 20 percent of small businesses fail annually. But the latest numbers are staggering.

I’ve been in touch with countless small business owners in the past two months. Most of their stories are beyond frustrating and sad.

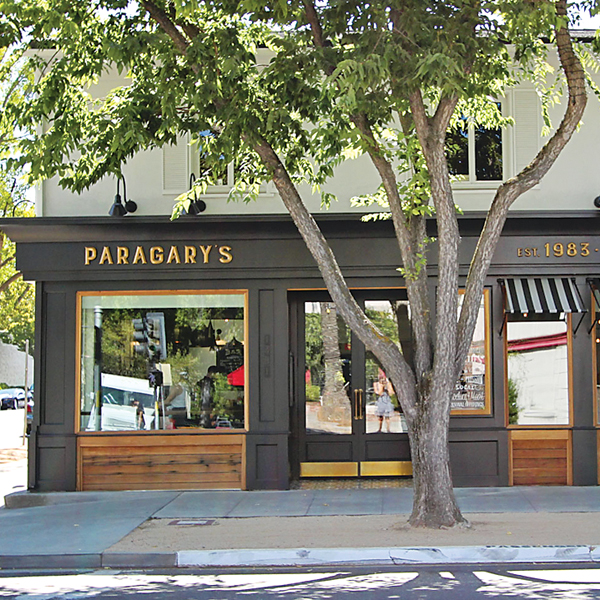

Restaurateur Randy Paragary, who has shaped local culinary tastes for 51 years with his restaurants and bars, attempted a carryout conversion when the shutdown began. Before the closure he employed 300. After two weeks, Paragary closed all eight of his sites, including three Café Bernardo locations. “We were losing money we couldn’t afford to lose,” he says.

He applied for Paycheck Protection Program funds, but wasn’t successful in the first round. Thankfully, his employees received support from state unemployment insurance. “They are getting their $450 state benefit, plus the $600 federal bonus, which is not pro-rated,” he says. “If your state benefit is $200, you still get the $600 on top of that.”

Many restaurant owners fear employees won’t return to work if their unemployment benefits exceed their work earnings. Paragary is not concerned. “The benefits may be a factor for some restaurants when they reopen, but I don’t think it will impact us,” he says. “The $600 benefit ends July 30. Let’s say we’re allowed to reopen June 1. Someone who would rather continue to get the benefit and not come back to work is taking a risk. There might not be a job for them on Aug. 1.”

He continues, “Not all restaurant jobs are created equal. Our people want to come back because they enjoy the experience of work. It’s stimulating to engage with their customers. They love cooking. They love working with top quality ingredients and expressing themselves through food. It’s their passion and profession. Frankly, if coming back and losing some benefits is a concern for people, maybe it’s best that they don’t want to come back.”

The bigger question for Paragary is whether his locations will have customers to justify the workers. “What is our occupancy going to look like?” he says. “We assume it will involve a spacing of tables. The No. 1 question is, what will the rules be? No. 2, what will be the public’s attitude in regard to safety? Customers will go to places where they are familiar and feel safe and trust the operators. I hope that includes us because of our history and reputation.”

Josh Nelson, CEO of Selland Family Restaurants, has another view. Selland restaurants include The Kitchen, Ella Dining Room & Bar, three Selland’s Market-Cafe locations and OBO’ Italian Table & Bar. Before the closure they had 360 employees.

Like Paragary, the Selland family tried carryout service but closed when they were unable to get clear direction from health officials on how to protect the safety of staff and customers. “It was an enormously frustrating runaround,” Nelson says of conflicting state and county orders.

Nelson says the group received PPP funds, but will likely return part of them. “It’s just not a useful loan for a restaurant. Our folks are able to get unemployment, plus the additional $600 a week, and for some of them it’s not even in essence fair to ask them to come back amid the uncertainty and risks we are facing.”

In late April, the group resumed carryout service at Selland’s Market-Cafes and OBO’ Italian. “We had time to understand the guidelines and develop an operational model to keep both our staff and customers safe,” Nelson says. “So far, it has been pretty effective. Mostly because we have always had a good base of our business in carryout so we know what we are doing.”

As the state begins to allow limited dine-in service, the Selland family will have to retool again.

Both Paragary’s and Selland’s restaurants have prime locations with beautifully designed interiors for pleasant and relaxing dining experiences. Changing those environments and retaining the experiences won’t be easy or cheap. Opening a restaurant requires a huge capital investment. Loans can take decades to pay off, in addition to ongoing and rising rents. Restaurant business models are based on serving capacity. Limiting capacity could be disastrous to notoriously thin margins.

It’s easy to overestimate profit margins. Says Nelson, “During our staff orientations, we do an exercise to spell out exactly how much profit is in a $7 cup of soup. They think it must usually be around $4, when, in fact, it is 30 cents. So we teach them if they drop the soup, just how many other cups of soup we must serve to make up for the loss.”

For retail shops, openings usually involve capital investment to create the interior. From there, the ongoing investment is inventory. The pandemic has created tremendous inequalities among retailers. Big box stores were allowed to stay open, with guidelines for safety. Home-improvement stores of all sizes continued to operate.

East Sacramento Hardware, owned by my friend Sheree Johnston, remained open with safety protocols and is busier than ever. Two miles away in Midtown, University Art, which sells art supplies and gifts, was required to close.

Both stores have roughly the same square footage. Both sell thousands of small and unique items. Neither has items available online for purchase. Both are designed for browsing. As a general retailer, University Art is now allowed to do curbside pick-up, but it’s not the same retail experience that created the store’s reputation. General manager Dave Saalsaa will do his best, but the unfairness is infuriating.

Our publishing business has been hit hard. Our entire income derives from small business advertisers. All have been impacted. Many have closed. In a good year—there haven’t been too many lately in publishing—our profit margin might be 2 or 3 percent of ad sales revenue.

Yet we headed into our April and May editions with probably 25 percent of our advertisers unable to pay us. PPP funds will help in the short run. But in our case, I had to reach into personal retirement savings to make up losses as I tried to sustain jobs for our 14 employees. We already have a very low-cost business model, so making cuts isn’t much of an option. I know at least a dozen small business owners who have done the same thing. Such decisions are physically and emotionally exhausting. But every day I meet someone who can’t imagine how our business has been affected by the pandemic!

It’s past time for state officials to throw out the hacksaw they used to create the rules to close and restrict small businesses. They need a scalpel and some nuance to plan for re-openings. Any business owner worth a damn knows they will be history without carefully managing for the ongoing safety of their staff and customers.

Small businesses are vital for our economic recovery. Government bailouts are helpful—when one can actually navigate them—and absolutely needed to help keep us alive in the short run.

But without a quick and sustained small business recovery, none of our lives will ever be the same.

Cecily Hastings can be reached at publisher@insidesacramento.com. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter or Instagram: @insidesacramento.com.