One of the most important questions I recall from childhood is, “What are you going to be when you grow up?” The question was not necessarily about jobs and pay. It was about life. Choosing a field of work defines who we are and how we live. It’s about what we accomplish and achieve.

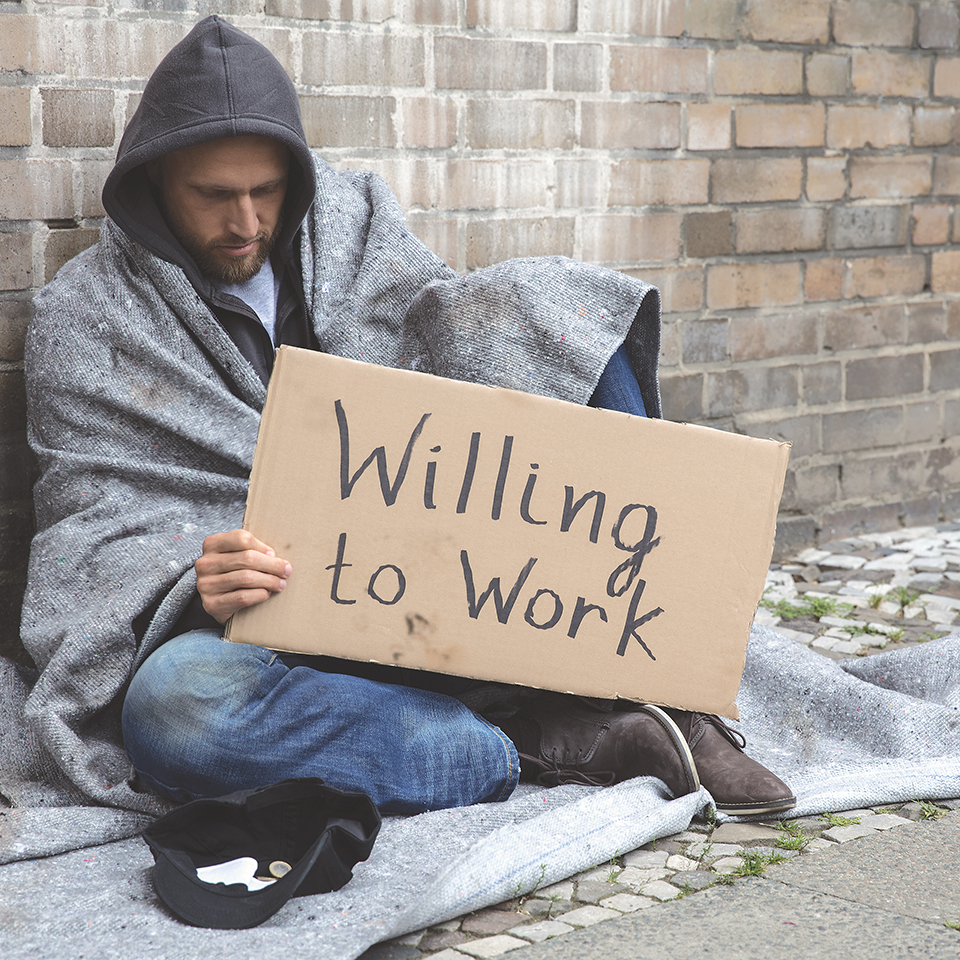

The opposite of work is not leisure or play. It’s idleness. The philosopher Aristotle declared happiness resides in activity, both physical and mental. People who lack the joy of work—the feeling of a job well done—miss something important.

In 1996, President Bill Clinton signed the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act. The bipartisan legislation substantially reconstructed the nation’s welfare system. The act ended welfare as an entitlement program. It required recipients to begin working after two years of receiving benefits. And it placed a lifetime limit of five years on benefits paid by federal funds.

As he signed the measure into law, Clinton said it “gives us a chance we haven’t had before to break the cycle of dependency that has existed for millions and millions of our fellow citizens, exiling them from the world of work. It gives structure, meaning and dignity to our lives.”

So why, as we face the catastrophe of homelessness, is the importance of work rarely if ever mentioned?

Commonly referred to as the “homeless” problem, the crisis we face is more accurately described as a problem of addiction and mental health. We need to ask: If we could house everyone on the street, would we solve the crisis? Sadly, the answer is no. The number of folks who receive housing and end up back on the streets is both telling and alarming.

Does having an addiction or suffering from mental illness preclude people from work? To some extent, the answer is yes. But not every addict or mentally ill person is unemployed and homeless.

A reader recently shared with me an article about a simple work program created by the former mayor of Albuquerque, New Mexico, to help homeless people in his city.

Throughout his administration, as part of a push to connect the homeless population to services, Mayor Richard Berry—the first Republican elected mayor in 30 years—would drive through his city and ask panhandlers about their lives. The poorest residents told him they didn’t want to be on the streets begging for money, but they didn’t know where else to go.

Instead of asking them to go out and look for work, Berry’s idea was that the city could bring the work to them.

Albuquerque’s “There’s a Better Way” program used this model to hire panhandlers for day jobs beautifying the city. In partnership with a local nonprofit that served the homeless, a van was dispatched to pick up panhandlers interested in working. The job paid $9 an hour, which was above minimum wage, and given lunch. At the end of the shift, participants were offered overnight shelter when available.

In less than a year since its start in 2015, the program gave out 932 jobs and cleared 69,601 pounds of litter and weeds from 196 city blocks. More than 100 people were connected to permanent employment.

Berry said panhandling was not especially lucrative and it’s demoralizing. But for some people it can seem like the only option. When panhandlers are approached in Albuquerque with the offer of work, most are eager for the opportunity to earn money, Berry said.

Folks in the program said they would rather earn money than have someone hand it to them.

The program provided a way to help resolve work impediments, including untreated medical conditions and lack of proper identification. Officials said many people in the work van were not aware of all the services available to them.

The mayor who followed Berry is winding down There’s a Better Way, but dozens of cities around the country want to copy the program. It’s a testament, Berry said, to the work mayors do regardless of political party.

Most experts agree the homeless crisis is not monolithic. No single magic bullet will solve it—including housing. People suffering from addictions, mental and physical illnesses, poverty, a lack of housing and work opportunities need separate paths to lead them out of the mess.

With all the money spent locally on homelessness, the Better Way program is something Sacramento should consider. People living on the streets and parkways generate huge amounts of trash and garbage. They create a public health crisis in some areas. Providing the opportunity and dignity of work to help clean it up is a win-win.

Cecily Hastings can be reached at publisher@insidepublications.com. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram: @insidesacramento.