Tucked among other news roiling our lives is a growing drumbeat about environmental justice.

President Joe Biden has promised his administration will keep it “in the center of all we do.” Health and Human Services director, former California Attorney General Xavier Becerra, spoke often about environmental justice. Becerra joined residents in San Bernardino to oppose plans to expand the airport for Amazon’s logistics needs.

And now, for the first time and as required by state law, there’s an environmental justice element in Sacramento’s 2040 General Plan—a component that calls for “an equity lens” when drafting development goals and policies.

What does environmental justice mean? And how might it shape Sacramento’s future?

Put simply, environmental justice—EJ for short—is about correcting the longstanding practice of neighborhoods with large minority and disadvantaged populations bearing the brunt of air and water pollution, noise and other adverse health effects from infrastructure projects.

As the California Department of Justice defines it, EJ “means the fair treatment of people of all races, cultures, and incomes with respect to the development, adoption, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.”

In a meeting of the city’s Planning and Design Commission, Commissioner Lynn Lenzi applauded Sacramento’s newfound religion.

“It’s been a topic of conversation for many, many, many years,” she says, “and it’s so great to see that it is now in the forefront of planning and that it actually will be incorporated into project discussions and hopefully in staff reports and conditions for approvals of many projects that are going in. I’m glad to see how far this has come and (that it’s) now in the forefront of our planning moving forward.”

Good intentions to right past wrongs. But some community activists I met have a different perspective.

For Oak Park resident Erica Jaramillo, a state employee and spokeswoman for the group Sacramento Investment Without Displacement, one EJ issue overrides the rest.

“Housing is the cornerstone of environmental justice,” she says. “And it can really set up someone to thrive or it can lead someone on a path through chronic homelessness and an inevitable encounter with drugs, sexual exploitation, violence. Then people are labeled at that point and it becomes really hard to get out of that.”

Others who reached out to me for a Zoom meeting addressed what EJ means to them.

Chris Jones is a health care and IT project manager from Colonial Heights. He’s president of Hope for Sacramento, an organization pushing solutions for Sacramento’s homelessness crisis. He took exception to a column where I promoted the city’s plan to allow duplexes, triplexes and four-plexes in neighborhoods historically zoned for single-family residential.

The controversial open zoning proposal is supposed to promote racial diversity in places such as Land Park and East Sacramento, while providing affordable housing options.

“The evidence that this actually is a good idea has neither been asked nor given,” Jones says. “There is nothing in the (General Plan) housing element that says relaxing the single-family zoning requirements would either lead to more affordable housing or more racial diversity. Research suggests it’s actually the opposite.”

Waverly Hampton III, a Sacramento State engineering student and owner of a small web development business, says he doesn’t see Sacramento doing enough to promote affordable housing.

“I moved here a little over a year ago,” he says. “From my perspective, there does seem to be this push to have single-family homes developed without thinking about if people can afford them, because the city is probably more concerned if people from the Bay Area can afford them, because that’s why they’re moving here. They can, but more and more people cannot.”

Jennifer Holden, a resident of Mangan Park near Executive Airport, organized our meeting. She spoke against open zoning after housing speculators called residents in her neighborhood and asked if they wanted to sell their houses, which are still relatively affordable.

“When you take an older neighborhood like this and (make it dense) in a short period of time, who will pay for infrastructure to handle that extra population load?” she asks. “I am very concerned about the relationship fabric of neighborhoods getting decimated. And no one is building the kinds of homes anymore that you find in our neighborhood.”

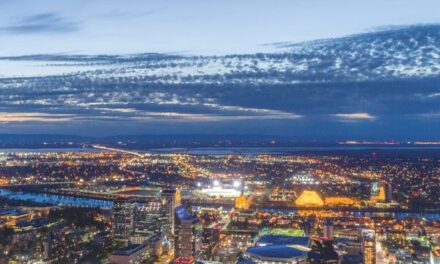

The big takeaway: Progress on amenities such as soccer stadiums and waterfront development is exciting, but with more people priced out of the housing market, such progress won’t provide equity for much of the population. Unless Sacramento does the hard work to provide more affordable housing, environmental justice discussions will be a lot of talk and not enough meaningful action.

Gary Delsohn can be reached at gdelsohn@gmail.com. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram: @insidesacramento.