Neighborhood Coyotes

Common Sense Actions Can Make Them Go Away

By Cathryn Rakich

January 2019

Suburban coyotes. Some people revere them. Some people fear them. Almost everyone wants them out of their neighborhoods. However, more and more coyote sightings and encounters between coyotes and domestic pets in the Arden-Arcade and surrounding areas are being reported, either on social media, at neighborhood meetings or to government agencies.

“It’s been an ongoing problem of coyotes in our yard since we moved back to the neighborhood in June,” says Michele Cable, who lives in Sierra Oaks Vista. Cable’s cat was attacked last year in the early morning by a coyote in the creek that runs along the west side of her property. The cat survived due to fast action by Cable, who screamed at the intruder and chased it away. “The coyote that attacked my cat was a mature, fat, well-fed coyote.”

While there are no statistics for local neighborhoods, countywide numbers verify the increase. In 2017, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Wildlife Services received 31 calls for technical assistance (from providing educational information over the phone to going on location to assess a situation) for Sacramento County. In 2018, by the end of November, that number had jumped to 55 calls.

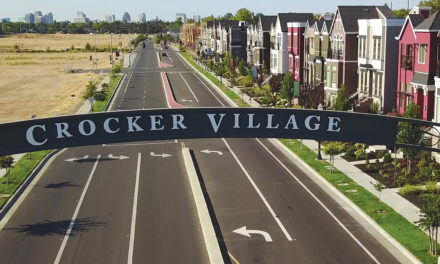

“I see coyotes regularly,” says Christina Riley, who also lives in Sierra Oaks Vista. “They are out at all times. Definitely an increase in coyote activity.” Sightings also have been reported in Arden Park, Wilhaggin and other nearby neighborhoods.

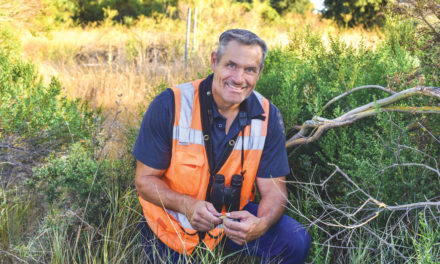

Why the increase? “People have a perspective that coyotes are out in the wild, but actually they are a highly adaptable species—they can survive and thrive in almost any habitat in California,” says Kyle Orr, public information officer for the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. “Coyotes are perfectly comfortable taking up residence in suburban areas because of the food sources.”

“The density of prey, such as cats, small dogs and rodents, are more readily available in urban centers as opposed to natural environments and pasture lands,” says Mark Ono, wildlife biologist and assistant state director for USDA Wildlife Services. “Other than humans, there are no natural predators of coyotes in this area.”

Coyotes, which belong to the dog family, average between 20 and 30 pounds and appear similar to a tan-colored Shepherd with a pointed muzzle, large ears, long legs and bushy tail. They are found throughout most of California, where breeding occurs mainly from January to March.

More human-coyote interactions occur “when young, inexperienced ‘teenagers’ start to venture off on their own and seek new territory,” Ono says. “There is also a period when females become aggressive to other canids and humans during the spring when they have young pups in the den.” This behavior is usually a defense of space or protection of pups, not random attacks.

The coyote diet consists mainly of mice, rats, squirrels, gophers and rabbits. “Coyotes have a lot of benefits from an ecological standpoint,” Orr says. “For example, they keep rodent populations under control.”

However, coyotes are intelligent predators and will shift their diet based on food availability, often indulging on insects, fruit on the ground, garbage and domestic pets. “If a coyote comes across a small dog or cat, they can and will kill it,” Orr says.

What about humans? While “attacks on humans are extremely rare,” according to Orr, the Department of Fish and Wildlife recommends that young children always be supervised by an adult when outside.

“We want people to be safe in their neighborhoods, but we also need them to use their best judgment and be aware of their surroundings,” Ono says.

Coyotes are most active at night and during early morning hours, but have been sighted strolling down area streets and thoroughfares in the middle of the day.

“They will actually forage during daylight hours as well, depending on the prey availability and behavior,” Ono says. “They change their behavior based on their location. These animals are highly adaptable, which is why they are so successful when it comes to urban living.”

Coyotes use trails, roads, creeks, flood-control channels and drain pipes to travel. “They are very common in our area. Possibly because we have large wooded lots to hide within and a system of creeks they use to travel,” says Riley, the Sierra Oaks Vista resident. To obtain water, they drink from street gutters, leaking sprinkler heads and outdoor faucets, birdbaths, pet dishes and swimming pools.

What should residents do to deter coyotes? Trapping and relocating coyotes is “akin to you being transported to Chicago with no food, no money and only the clothes on your back,” reports the City of Sacramento Animal Care Services. Relocated coyotes must compete with other animals that have established territories. And coyotes will quickly replace each other if one is removed. “All you’re going to do is move the problem to another neighborhood,” Orr says.

Government agencies and wildlife enthusiasts universally agree—to eradicate or reduce coyotes in the suburban/urban environment, residents must do two things: eliminate all food sources (see “What You Can Do”) and scare them away.

“Coyotes are very, very clever. They adapt and they learn,” Orr says. “People can take common-sense precautions.”

Coyotes generally avoid humans. “However, the presence of a free buffet in the form of pet food, compost or trash can lure coyotes into yards and create the impression that these places are bountiful feeding areas,” reports the Humane Society of the United States. “Without the lure of food or other attractants, their visits will be brief and rare.”

And there are people who intentionally feed coyotes. Less than a quarter mile from Cable’s home in Sierra Oaks Vista is a vacant, boarded-up house where someone leaves large pans of dog kibble for coyotes. “It is illegal to feed coyotes and it always harms the animal,” Orr says. “They are perfectly capable of finding food on their own. When people feed coyotes, they become habituated and associate people with food. And they lose their fear of humans, which leads to more negative encounters with humans.”

Hazing (using a variety of non-lethal scare techniques) is one way to condition coyotes to avoid humans. When coyotes become habituated, hazing can re-instill the natural fear of humans.

“If residents walk their small dogs on leash around the neighborhoods, they need to be aware of their surroundings—just as they would any other time,” Ono says. “In the event they see a coyote, they should shout, clap their hands, throw rocks, etc. The point is to make a lot of noise and scare the coyote off.”

“The coyote I saw when I was on foot with my two Labradors observed us and only moved when I clapped and shouted,” Riley says.

Other hazing and deterrent methods include flashing lights, banging pans together, and scattering mothballs or ammonia-soaked rags around the yard.

“It’s important to remember that seeing a coyote doesn’t mean that an attack is imminent or that your pet, child or yourself is in danger,” Ono explains.

“We really want people to understand that we share habitat with coyotes,” Orr says. “There are steps they can take to ensure their safety and the safety of their family.”

The University of California Cooperative Extension has developed a statewide website to collect information on coyote encounters in California. To submit a coyote sighting, go to ucanr.edu/sites/coyotecacher. For more information, visit www.wildlife.ca.gov/keep-me-wild/coyote or humanesociety.org/coyotes.

Cathryn Rakich can be reached at crakich@surewest.net.