Farm to Consumer

West Sac business helps small farms distribute their harvest

By Tessa Marguerite Outland

November 2020

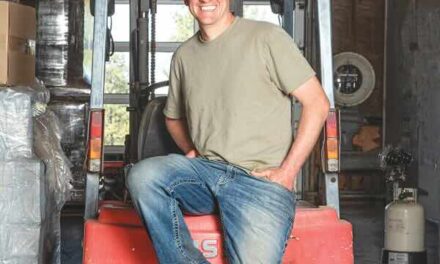

When Michael Bosworth started a grassroots food distribution business in 2006, he was thinking small. Small enough to notice that the organic rice farm around the corner and a fancy sushi restaurant in East Sac could be partners. Yet big enough to consider the stability and growth of future farmers and generations of farms.

Bosworth, founder and CEO of Next Generation Foods, is a fifth-generation farmer. His family’s involvement in beef cattle evoked Bosworth’s interest in agriculture at a young age. He holds a BS in crop science and management, and an MS in agricultural and resource economics, both from UC Davis. For Bosworth, some days are spent as a farmer out in the field before the sun rises, and others as a salesman in his West Sacramento office.

Next Generation Foods is farmer-owned and prioritizes relationships between farmers and the food service industry. When Bosworth started the business, he offered only one product: organic white Calrose rice from Rue & Forsman Ranch, his family’s farm in Olivehurst. The pearly white grains are frequently used in Mediterranean and Asian dishes. One of the first wholesale customers to buy this high-quality rice was chef Billy Ngo, founder of Kru Contemporary Japanese Cuisine in East Sacramento.

As Next Generation Foods’ business increased, the company reached out to farmers at E & A Farms in Davis, Pleasant Grove Farms and Consumnes River Farms in Thornton to add more items to the distribution list. Next Generation Foods now offers approximately 16 varieties of rice.

“We’ve had to take a lot of risk, but in doing so we’re able to supply our customers with virtually every kind of rice you could ever ask for. I’m pretty proud of that,” Bosworth boasts. In his pantry at home, Bosworth has more than 50 pounds of various types of rice from all over the world.

Before the food service industry entered into COVID-19 hibernation in mid March, Next Generation Foods was selling to well-established customers like Golden 1 Center and tech campuses in the Bay Area that supply premium food to their employees at little to no cost. Within a week of the global pandemic, the market flipped to retail and online ordering.

In late August, Bosworth reported that his business had sold more than 100,000 units (2-pound bags of rice) in the last five months. Previous years, Next Generation Foods sold about 2,000 units per year. “It was a huge shift in our model,” Bosworth says. “Everybody’s had to adapt. We’d have been in really rough shape if we hadn’t.”

The “big picture” for Next Generation Foods is to help California’s future farmers thrive and succeed at improving how agricultural products move through the state’s food-supply chain. In Sacramento, there has been an increase in awareness of the necessity, not just the charm, of farm-to-fork practices.

A 1981 summary report by the Department of Agricultural Economics, UC Davis, found that corporate farming in California had been on the rise since the early days of the state’s agricultural enterprise. The report states that, according to the Census of Agriculture, in 1954 there were almost 4.8 million farms in the United States, and the average size was 242 acres. By 1978, there were 2.4 million farms, with an average size of 416 acres, almost twice as large.

Smaller farms were rapidly being swallowed up by large corporations in order to mass produce agricultural products. More recent information from USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service shows a continued trend of corporate farming.

However, from 2018–2019 the number of small farms (under 179 acres) in California in an economic sales class of under $10,000 increased by approximately 800 farms. This is a huge leap considering that across the country the total number of similarly classified farms actually decreased by about 1,150.

In Sacramento, farms with fewer than 9 acres made up 41 percent of the total number of farms, according to the most recent 2017 USDA report.

“Overall, farming is becoming more efficient in the use of resources and providing very high-quality, safe food to consumers at fair prices,” Bosworth says. “However, competition from other countries is strengthening as well. And with lower cost of labor, and much lower regulatory and food-safety compliance costs, competition from imported goods will continue to pressure California farms.”

If consumers like chefs and farmers market foodies continue to crave that fresh farm-to-fork food, then these small generational farms can keep planting, growing and distributing their harvest well into the future.

Tessa Marguerite Outland can be reached at tessa.m.outland@gmail.com. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram: @insidesacramento.