As the pandemic devoured chunks of humanity, one recreational holdout stood tall, defiant and immune: the golf course. Designed for distance and unfettered by walls and ceilings, golf became the perfect antidote. A vaccine is not required to shoot par.

In Sacramento, golf played through. While lockdowns ended fan experiences and demolished profit margins across the sports landscape, Morton Golf, which runs the city’s four municipal courses, didn’t miss a tee time.

“We never closed,” says Ken Morton Jr., operative heir to a family business that tracks its golf lineage to the hickory-shaft mashie era. “Sacramento was the only county in California that didn’t close golf.”

The perseverance of local muni golf over the past 15 months is no accident. As COVID-19 began to shutter everything from neighborhood coffee shops to the NBA, Morton sat down with his head professional, Mike Woods, and adviser Rob Fong, a former City Council member.

They devised a six-page list of safety protocols, an exhaustive addendum to winter rules that covered everything from golf cart occupancy to ball washers. In golf argot, the new procedures were a compendium of pandemic-specific preferred lies.

“We got in front of the county health department and our safety protocols were approved without changes,” Morton says. “Pretty soon, other counties began to use our list, and eventually other states. Sacramento County was the model for golf.”

Then a curious thing happened. People began to flock to golf courses. Homebound and frustrated by restrictions that pushed many recreational opportunities out of bounds, residents went to the garage and dug out their golf bags. They rediscovered the game.

“Nationally, golf rounds are up anywhere from 30 to 35 percent,” Morton says. “We are within that range. It’s impressive, given that golf has been flat or maybe lost a point or two since the years when Tiger Woods got a new generation interested in the game.”

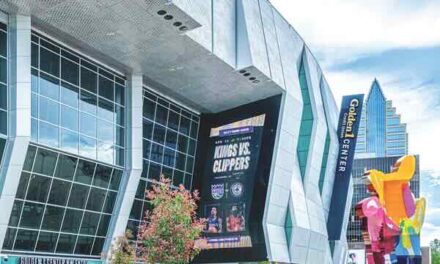

The four city courses—Haggin Oaks, Bing Maloney, William Land and Bartley Cavanaugh—all enjoyed consumer upticks. Morton didn’t launch a marketing drive. The golf surge is organic.

“We would never want to flaunt we were open while other industries weren’t,” he says. “We just kept our heads down and tried to provide as safe an environment as we could. People just kind of found the sport. It was kind of remarkable.”

Aside from the low-keyed approach to golf’s pandemic defiance, Morton Golf is a marketing machine. A program to bring women into the sport has introduced more than 1,000 new players to city courses. Women ambassadors oversee recruitments.

“Historically, our game has driven out as many people as it attracted,” Morton says. “Now the women ambassadors drive everything and the men just stay out of the way.”

Young golfers are another key audience. Morton Golf sponsors programs for African American and Latino youths, supplying equipment and travel funds if families lack resources. All kids play free with a paying adult.

A comprehensive golf education center is being teed up at Johnson High School. Programs dedicated to Special Olympians, disabled veterans and blind golfers are supported by a Morton foundation that raises around $250,000 annually.

Then there are the golf courses. The easiest way to drive players from the game is with subpar facilities. Here’s where Morton Golf celebrates its legacy and presents customers with municipal courses that can match many country clubs—for a fraction of the cost.

Twenty years ago, the city turned over maintenance of its four public courses to Morton. Previously, Morton ran the pro shops and cafes and left the mowing to city workers. Improvements instantly appeared when Morton stepped up. Millions of dollars were spent on new groundskeeping equipment. During the pandemic, Morton invested another $1 million in upgrades and mowers.

Golf is wired into the Morton nervous system. Morton’s father, Ken Senior, went to work for the city’s original golf pro, Tom LoPresti, in 1958. Both were renowned PGA teaching pros. Ken Senior retired this spring at age 81.

As the pandemic fades, Ken Junior is reopening weddings and banquets at the golf courses. And he’s sampling a sport that involves a different type of water hazard.

“My wife and I bought a kayak,” he says. “We won’t just let it sit in the garage.”

R.E. Graswich can be reached at regraswich@icloud.com. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram: @insidesacramento.