A friend was telling me how much he enjoyed small, low-profile sporting events. He mentioned going to Sacramento State games. I know the feeling.

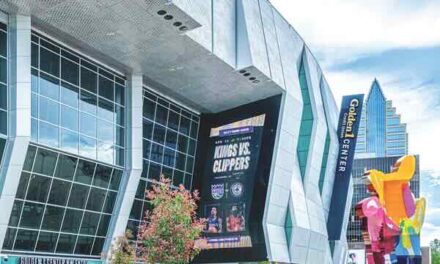

I prefer a summer night at the River Cats over the frenzied, obnoxious environments of NBA arenas and NFL stadiums. Sportswriters are supposed to get excited by big showdowns and great athletes.

They wore me out.

When I covered pro basketball years ago, I was glad when the NBA Finals ended in four or five games rather than seven. A quick series meant I could go home sooner. Not long thereafter, I stopped being a sportswriter.

Gambling at the city’s dog racing track scandalizes Sacramento in 1932.

Happily, Sacramento provides warm greetings to second-tier sports. The city welcomes basement-level shows.

The World’s Strongest Man contest became an annual celebration on Capitol Mall until last year, when Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, stole our barbells. I miss the big guys.

Decades ago, I loved writing about indoor soccer and football at Arco Arena. There was a wonderful semi-pro hockey team, Sacramento Rebels, at Ice House on Bradshaw Road. And countless obscure boxing and wrestling matches at Memorial Auditorium.

The more enigmatic the game, the more organic the joy.

I wasn’t around for weird sports that blew through town in the old days, those true mid-20th century misfits. Imagine watching sprint cars or motorcycles scramble around a narrow, dusty quarter-mile track at Hughes Stadium. Our ancestors savored it.

Another local event I missed was greyhound racing. I bet even scholarly local sports fans know nothing about Sacramento’s dog track.

The place was called K-9 Park. A wooden grandstand held 7,000 fans at the corner of Fruitridge Road and Stockton Boulevard, where Fruitridge Shopping Center sits today. Promoters spent $75,000 constructing a fancy dog palace. A mountain of money in 1932.

K-9 Park was controversial before it opened. Greyhound racing wasn’t exactly illegal—sportsmen raced hunting dogs after prey in the Yolo Causeway—but gambling was a crime. Promoters behind K-9 Park devised a clever way to let people bet on races without actually betting. Sort of.

The scheme required customers to buy into something called the “option system.” Gamblers purchased a $2.50 “preferred option” or a $2 “secondary option.” In theory, options were ownerships in greyhounds.

If you bought a preferred option and your dog won, you’d get your money back plus interest determined by a K-9 Park employee who was fast with odds. A $2 option paid off for the top two finishers. If your dog ran worse than second, your option was worthless.

Everyone knew the option system was a joke—semantics to evade police. In San Francisco and Alameda counties, authorities called it a “racket” and banned dog racing.

But Sacramento County District Attorney Neil McAllister wasn’t so sure. He said, “I have heard that option betting is a successful evasion of the law, and it’s questionable whether it is legal or not.”

Opening night Aug. 1, 1932, drew crowds that required Highway Patrol to direct traffic on Stockton Boulevard. Days before, promoters from the Sacramento Amusement Company visited gin mills around town and handed out hundreds of free tickets.

Customers filled the silver-painted grandstands. People loved to watch greyhounds chase a mechanical stuffed rabbit. Options went unsold.

K-9 Park staffed 30 option windows that first night. As the two-month meet progressed, window staff dwindled to 18, then five. Fans enjoyed the dogs. But they didn’t buy options.

Stung by low sales, Sacramento Amusement Company slowly went broke.

Law enforcement presented another hurdle. Sheriff’s deputies arrested an option seller, John Garritty, who ran window No. 4. The jury deliberated 17 minutes and found Garritty not guilty.

The verdict upset civic leaders. An outraged Bee editorialist wrote, “The district attorney’s office from the first had no intention of interfering with the dog-racing racket.”

Where the law failed, economics prevailed.

Without enough bettors, the track closed after one season. K-9 Park was renamed New Night Speedway for auto racing. It burned down in 1935. Fire Chief J.C. Taylor suspected arson.

R.E. Graswich can be reached at regraswich@icloud.com. Follow us on Facebook and Instagram: @insidesacramento.