Final Toot for Trolley?

How cross-river streetcar ran out of track

By Craig Powell

March 2019

It’s hard to declare a municipal streetcar project dead. Many streetcar projects around the country have been given last rites over the years, only to rise like Lazarus from the ashes. Streetcar projects are, for some reason, extremely hard to kill.

Sacramento’s streetcar project seemingly died on more than once occasion, only to return in some new incarnation. But the project’s most recent crash is likely to be the last.

In January, construction bids were finally opened for the long-planned 4.4-mile circulating route that would allow streetcars to travel from West Sacramento City Hall, across the Tower Bridge and east to maybe 19th Street. Project designers estimated the cost for tracks, overhead wires and associated equipment at $108 million.

For months, the rumor mill hinted the bids would land well above the estimate. Even then, many observers were stunned when the three bids were opened. The lowest was $184 million—or $76 million above estimates.

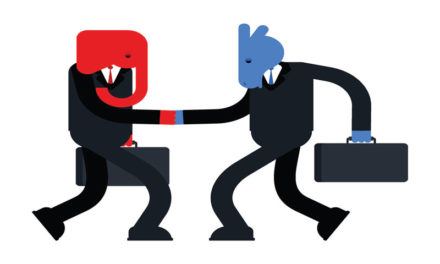

How is it possible that project managers could be so wildly off the mark? Hubris played a major role. The project—a complex partnership among the cities of Sacramento and West Sacramento, Regional Transit and Sacramento Area Council of Governments—was the brainchild of ambitious urban planners who saw other U.S. cities rush to build “modern streetcar” projects, largely in response to the availability of new federal funds under the U.S. Department of Transportation’s “Small Starts” program.

With “Small Starts,” the feds pick up half of the cost of building such systems, but none of the operating costs. Fifty-percent match programs are like crack cocaine to local planners: almost impossible to resist.

Would such a project in Sacramento even be considered if not for the lure of the 50-percent federal match? Not a chance. Which is instructive: If a project lacks sufficient merit to justify a city coughing up the money to build it, why should it be built?

American cities such as Sacramento have access to municipal bond markets. If they properly manage their bonding capacity, they can cheaply raise the cash to build such systems on their own. But in reality, projects such as the Tower Bridge streetcar make no sense unless half the cost is “free,” picked up by federal taxpayers.

And municipal planners feel a profound anguish when they pass up opportunities to grab “free” federal money. With federal dollars beckoning, economic common sense and judgment melt. It’s bureaucratic human nature, I suppose.

Midway through the Sacramento streetcar saga, the federal government raised the maximum amount it was willing to give cities to build streetcar projects, from $75 million to $100 million. What was the response of our local officials? They promptly increased the size and scope of the streetcar project, going from $150 million to $200 million.

Sacramento City Councilmember Steve Hansen was quoted in The Sacramento Bee, April 26, 2016, saying, “We didn’t want to leave money on the table. If we want to ask for more, we have to show a bigger project.”

You can see the problems with such logic. The project grew not because it merited expansion, but because more federal dollars became available.

How was the streetcar project expanded? By creating an unnecessary 1-mile spur in West Sacramento along the Sacramento River south of the Tower Bridge to the Pioneer Bridge at a cost of $25 million, and by proposing to move Light Rail from K Street three blocks north to H Street so the streetcar could run down K Street, which would cost another $25 million.

Why did they want to move Light Rail to H Street? Because merchants on K Street thought a streetcar would look better than Light Rail trains (I kid you not). Did anyone stop to consider the inconvenience of such a move on Light Rail commuters, most of who work south of K Street? Apparently not.

But the $50 million streetcar expansion scheme created another problem. How to come up with $25 million in additional local matching dollars to win the $25 million in additional federal dollars?

The answer was state government, which was soon visited by city officials, hat in hand. Local authorities had already lined up $30 million of state funding from cap-and-trade funds. They finagled the state to provide another $25 million from the sale of high-speed rail bonds.

To juice passage of the high-speed rail bond ballot measure several years ago, rail proponents promised local jurisdictions along the proposed high-speed route a princely share of bond proceeds. Regional Transit was in line to collect $25 million—but the money could only be used for rail projects in the RT service area.

That presented RT with a choice: it could use the high-speed rail money to begin replacing its aged and obsolete fleet of Light Rail cars (a $200 million-plus unfunded liability) or it could use it as the local match to secure $25 million more in federal funding for the streetcar.

The responsible thing to do would have been to use the money to replace ancient Light Rail cars. But the fix was in: Sacramento city councilmembers on the RT board used their collective influence, along with the personal urging of Mayor Darrell Steinberg, to approve spending the money on the streetcar project.

Why didn’t Sacramento officials ask property owners in the vicinity of the proposed streetcar to tax themselves to cover the local “match” needed to secure federal funding? They did. In June 2015, the city asked Downtown and Midtown voters to approve a property tax assessment to raise the necessary local dollars for the streetcar. As a special tax, it required a two-thirds majority to pass. After a spirited campaign, the streetcar tax missed its two-third mark by a 20-percent margin, with 49 percent voting for the tax and 51 percent voting against it.

Did the city respect the democratically expressed will of voters and drop the streetcar project? Not in this town. On the next day after the vote, Hansen announced city officials would hunt for a “Plan B” to fund the local match. Plan B was to tap state cap-and-trade and high-speed rail bond money.

With the jaw-dropping construction bids having injected an apparently fatal dose of reality into the streetcar project, taxpayers and commuters can only hope it stays dead. The last thing Sacramento needs is a $184 million streetcar named Lazarus.

Craig Powell is a retired attorney, businessman, community activist and president of Eye on Sacramento, a civic watchdog and policy group. He can be reach at craig@eyeonsacrament.org or (916) 718-3030.