What Price Glory?

Steinberg’s appetite needs reality check

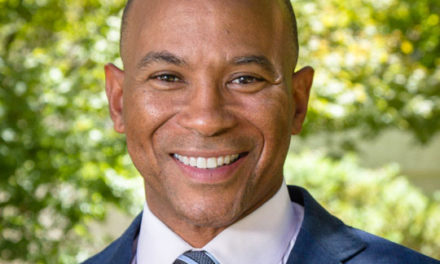

By Craig Powell

April 2019

At his State of the City speech in February, Sacramento Mayor Darrell Steinberg said, “Sacramento can in fact have it all.” What he didn’t say was how the city will pay for it all.

In the warm afterglow of his successful campaign to pass the Measure U sales tax, Steinberg exhibited gross overconfidence in the ability of local government to solve the most complex and entrenched social problem of our day—poverty—while losing touch with the city’s inherent financial limits.

In his speech, Steinberg called for the city to put 80 percent of new Measure U money (about $40 million a year) for five years into an “economic trust fund” to invest $200 million directly in “economic equity” in our neighborhoods. The irony is that the burden of his new 1-cent sales tax falls most heavily on those the mayor sincerely hopes to help with his “inclusive economic growth” program.

If there’s a silver bullet solution to the problem of poverty, most policy experts would agree it lies not in transfer payments, corporate welfare, subsidized housing or redevelopment spending, but in preparing our young for productive and prosperous futures through excellent schooling. But education is the one policy arena where the mayor has been AWOL.

Steinberg has done nothing to intervene in the tragically failing Sacramento City Unified School District, which is on track to run out of cash and get taken over by state receivership in November. In fact, the mayor’s sole intervention in the school district has been to exacerbate its crisis by midwifing an irresponsible labor contract in 2017 with teachers.

The contract handed out significant raises to teachers, but did nothing to control the huge health care costs that are concussing city school finances, as reflected in the stupefying $700 million unfunded liability for retiree health care.

ONE-TIME MONEY: CHRISTMAS MORNING AT CITY HALL

As the mayor put it in his Jan. 29 budget memo to the City Council: “I strongly believe that in our first two years together we have laid a solid foundation on every key challenge and opportunity facing our changing City. 2019 must be the year we shift from foundations to breakthroughs.”

The city has about $35 million in “leftover” money, sometimes called “one-time” money. This includes about $15 million in leftover money from last fiscal year, and $20 million in reserves from the half-cent sales tax under the original Measure U.

The council has a longstanding practice of taking money left from prior fiscal years and using it to shore up finances, usually by socking money away in Economic Uncertainty Reserves (now 10 percent of the general fund, compared to a reserve of more than 20 percent at the onset of the Great Recession). Alternatively, the city has modestly paid down its unfunded retirement liabilities (now nearing $1 billion).

The city also typically uses leftover money for long-term investments. The council has a written policy not to use one-time money to pay operating costs. This year, the policy was largely shredded.

Of the $35 million, $11 million is being spent on overtime pay, cost overruns, increased staffing, two fire academies and minor equipment purchases. The memo said $8 million “of one-time money (is being spent) to show the neighborhoods the potential of their transformational decision last November,” meaning a reward for approving Measure U. Of this $8 million, $2.1 million would be used to launch six new programs, mostly focused on youth.

But the biggest item in the mid-year spending spree is a whopping $16 million to open and operate eight new 100-person homeless shelters over the next two years. This would be augmented with $12 million in current and anticipated state dollars, $10 million in private-sector funding (mostly from health care systems), for a total of $40 million for shelters (it’s not clear where the final $2 million would come from). That equates to an eye-popping cost of $50,000 to house (on a cot) and feed each homeless person for two years.

The proposal drew pushback from Councilmembers Angelique Ashby, Larry Carr and Allen Warren, who questioned whether spending so much on shelters made sense in the face of other priorities, such as police, fire and parks, and expressed concern about where the money to operate the shelters would come from after two years.

There’s also the question of a $63 million hike in the city’s annual pension payments to CalPERS. There’s no provision for how the city will pay that bill.

The City Council is shoveling nearly $35 million of one-time cash out the door while ignoring the fact that forecasts show Sacramento will experience $30 million in annual budget deficits to the general fund in just three years. The forecasts make no allowances for a future recession.

The other striking feature of the mayor’s shelter plan is how he’s trying to shift responsibility for the location of eight homeless shelters from the city itself to individual councilmembers. Clearly, Steinberg wants councilmembers to take the heat for choosing shelter sites in their districts—along with potential impacts the shelters may have on neighborhoods.

In other words, it’s the mayor’s homeless plan, but each councilmember gets the political headache.

That may be one reason why only two of the eight members have, as of our publication deadline, publicly proposed shelters in their districts. The mayor’s closest ally, Jay Schenirer, is proposing a shelter in the parking lot of the Florin Road Light Rail Station, kitty-corner from Luther Burbank High School, next to a mobile home park.

Our sources tell us the folks at Regional Transit are less than thrilled by the prospect of having a 100-person homeless shelter a few yards from a station on a route that has struggled to achieve anticipated ridership levels. The angst is understandable given the major progress RT has made under general manager Henry Li in improving the security and cleanliness of Light Rail trains and stations.

We’ve received no word yet on how school administrators or parents of Burbank students feel about a homeless shelter within a stone’s throw of campus.

In District 3, Councilmember Jeff Harris is proposing that a shelter be built at Cal Expo. The site is located in the southeast corner of the Cal Expo parking lot, near the intersection of Ethan and Hurley, a short walk from Arden Fair Mall.

One of the biggest objections North Sacramento residents had to the opening of the so-called “Winter Triage Shelter” on Railroad Drive 15 months ago was they felt blindsided by the lack of adequate notice from the city. When assistant city manager Chris Conlin was quoted in a Sacramento Bee article saying, “All council members have identified potential shelter sites in their districts to staff,” but failed to publicly identify the sites, we grew concerned.

Were city officials playing “hide the pea” on exactly where councilmembers intended to place homeless shelters to avoid arousing neighborhood opposition until it was too late for residents to do much about it?

Councilmember Allen Warren, whose North Sacramento district is most impacted by the operation of the winter shelter, urged colleagues at a recent council meeting to announce their potential sites. “We all have to play a major role in this process,” Warren said.

When Warren’s plea fell on deaf ears, Eye On Sacramento filed a request under the California Public Records Act asking the city to divulge records on the sites proposed by each councilmember.

Unsurprisingly, the city failed to deliver the information by our publication date. From this silence, the public can infer city leaders plan a repeat of the short-notice neighborhood ambush they used in North Sacramento, this time on other unsuspecting Sacramento neighborhoods.

Craig Powell is a retired attorney, community activist and the president of Eye On Sacramento, the local government watchdog and policy advisory organization. He served as chair of the No On Measure U campaign. Powell can be reached at craig@eyeonsacramento.org or (916) 718-3030.