Nathaniel S. Colley died in 1992, but he’s having an excellent 2021. His home on Pleasant Drive in South Land Park has been declared a historic landmark, along with his office on S Street. A new school on Gerber Road is named for the civil rights attorney.

Tributes to Colley invariably mention his work to end housing discrimination and his status as the first African American lawyer to practice in Sacramento. That would be January 1949, when he was admitted to the California Bar. Six years later, he built his home at 5114 Pleasant Drive, integrating a whites-only neighborhood.

But Colley had another passion that usually goes ignored. He was a sportsman and mad about horse racing.

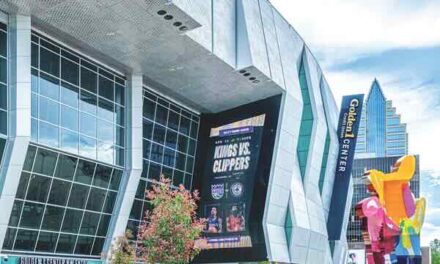

He purchased box seats at Cal Expo and rarely missed a day’s action during the State Fair thoroughbred meet. When night harness racing became a Sacramento phenomenon in 1971, the best place to find Colley was not at his office or home, but the racetrack.

Colley was a bold horseplayer. He loved to search the Daily Racing Form or harness program for long shots. He believed he could conjure opportunities missed by other bettors.

I visited Colley’s box and Turf Club table several times and watched him in action. Judging from the torn betting tickets that littered the floor around his feet, I figured Colley was like many horseplayers. His long-shot dreams dissolved as his horse faded down the home stretch.

Colley suffered defeat like any bettor, but he was no common horseplayer. He served seven years on the California Horse Racing Board. He bred hundreds of racehorses at Priscilla Bell Farm, his 122-acre ranch in Elk Grove.

And in 1984, Colley kept harness racing alive in Sacramento by taking over the operation and running the show. Sadly, his Cal Expo harness season was a fiasco. It became a rare and costly failure in the Colley legacy.

Colley resigned his seat on the racing board before the 1984 harness meet. Partnering with a food concession manager named Scott Esparza, Colley was the brains and financial heavyweight behind the operation. But he wasn’t a true heavyweight.

“What I’m saying is that I’ve had to exhaust my credit with my bank,” Colley told friends as his harness meet began. He borrowed $350,000 to ensure the track met minimum requirements for cash on hand.

The odds were stacked against Colley. Track operators took small profits from parking, ticket sales and wagers made by customers. The real money was in food and drink.

But Colley didn’t preside over concessions. Cal Expo sold the track’s hot dog and beer contract to Ogden, a global food concessionaire that today operates as Aramark. Colley despised Ogden.

“We put on the show and people come here to eat and drink beer. The profits are going to Ogden and they are running a tacky operation. It isn’t first class,” Colley said. He insisted Ogden failed to spend a promised $600,000 in track upgrades. “All Ogden has done is patch up the worn railings with tape. They’re just not taking care of the public.”

Other problems emerged. Colley installed new wagering machines, but the equipment had glitches. Bettors grew frustrated. Several races were interrupted when the power grid failed at Cal Expo. Colley ended up losing money. “We wound up substantially in the hole,” he said. The 1984 harness season was a long shot that finished dead last.

Colley continued to breed thoroughbreds at his Elk Grove ranch. His first horse—a filly named Najermape—was a gift from a client to Colley and his law partner, a future judge named Mamoru Sakuma. The filly debuted at Vallejo and won her first race. That was 1958. Colley was hooked.

“The judge and I were so new we didn’t realize we were supposed to go to the winner’s circle,” Colley said.

Brain cancer ended Colley’s life at age 73. He died at Priscilla Bell Farm near the stables he loved so much.

R.E. Graswich can be reached at regraswich@icloud.com. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram: @insidesacramento.