If Walls Could Talk

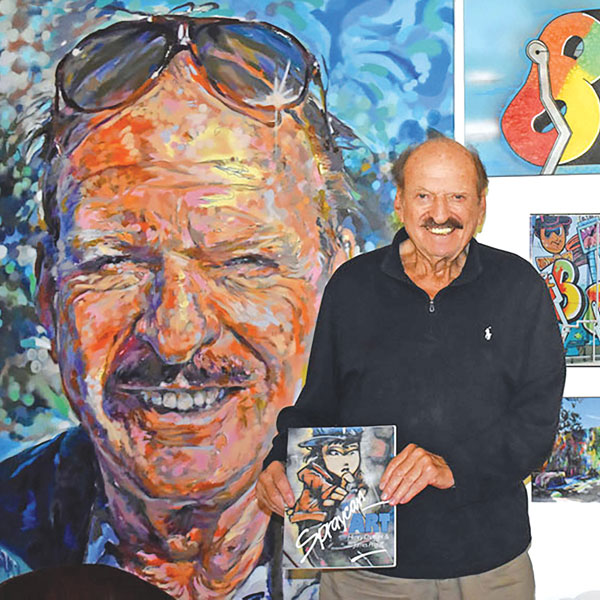

Campus Commons photographer captured street art movement

By Jessica Laskey

August 2021

When Jim Prigoff began photographing street art in the late 1960s, he didn’t realize he was documenting an artistic revolution. But he knew there was something special about the spray-can art popping up on walls all over the world.

Prigoff, who became internationally renowned for his photos of graffiti, died in April at his Sacramento home. He was 93. Several weeks before his death, he granted an introspective interview to Inside Sacramento.

“The end of the 1960s was a time of foment,” said Prigoff, a New York City native who lived in Boston, Chicago and San Francisco before settling in Sacramento in 1989. “Everyone was going to the walls to express different ideas and concepts you didn’t get in the news.

“People were talking about (graffiti) as criminal, but I had a sense that something was happening that was actually very positive. I started to take a few pictures and it turned out I was on the right track. Street art has developed into the most significant art form of the last 40 years.”

Prigoff had an eye for capturing culture. After graduating from MIT in 1947, he and his wife Arline embarked on an 11-week trek to photograph natural wonders in the U.S. and Canada. That led to more travels abroad, which led to Prigoff joining The Explorers Club, an international multidisciplinary professional society founded in 1904 to promote scientific exploration.

According to the club’s website, “Members have been responsible for an illustrious series of famous firsts: first to the North Pole, first to the South Pole, first to the summit of Mount Everest, first to the deepest point in the ocean, first to the surface of the moon.”

This year, The Explorers Club named Prigoff one of the “Fifty People Changing the World the World Needs to Know About” (also known as EC50). Prigoff was selected from more than 400 nominations from 48 countries in recognition of his immense contributions to the documentation—and legitimization—of street and urban art.

Through photography, writing, lectures and exhibitions, Prigoff showed the world that even though this artwork was done with spray paint on subway cars and railroad retaining walls, it wasn’t less artistic or culturally significant than other art forms.

“Different art is usually rejected initially, like the Impressionists in Paris,” Prigoff said. “Originally, it was about inner-city kids staking out a little bit of territory. They’d see cars with fancy license plates, but a kid doesn’t own a car. He can’t put his name on a license plate. So how does he get recognition? He puts his name on a wall. It’s a different way of saying, ‘I’m here. I’m a significant person.’ It’s a way of communicating. And now, what was once criticized as vandalism is being sold for millions of dollars.”

Prigoff maintained friendships with many of the “writers” (street artists) he photographed. He was proud to influence current generations, especially through his book “Spraycan Art,” co-written with Henry Chalfant in 1987.

“Many of these kids come out of gangs,” the Campus Commons resident told Inside. “Many of their friends have died, so they join a fraternity of the streets—a street group that paints together—instead. Many young people come up to me and say, ‘Your book saved my life. It took me out of a dangerous place.’”

Prigoff was pleased to see his favorite art form in Sacramento. He mentioned murals by Shepard Fairey at 16th and L streets, Apexer at Seventh and J, Bryan Valenzuela at 28th and R, and new pieces from Wide Open Walls each year. In these works, he saw the same energy he fell in love with nearly 60 years ago.

“It’s a very ephemeral art form,” Prigoff said. “It can never be duplicated. It’s one of a kind and one of a time.”

Jessica Laskey can be reached at jessrlaskey@gmail.com. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram: @insidesacramento.