In Tune Carmichael

By Susan Maxwell Skinner

April 2019

No Kidding

Goat farmer and family welcome an early spring

A kid explosion in Kath Friedrich’s goat herd brought an early spring for the Carmichael mom. In barns at her Rio Linda farm and at home in Carmichael, Friedrich’s pregnant goats delivered sooner than expected. “The moms were all on course to deliver in March,” says the former law professor.

“Then the big rains came in February. One of my first-time moms birthed three kids at Rio Linda. Two didn’t make it. The surviving baby was weak. I brought mom and baby back to Carmichael. I milked the mom and bottle fed her little one five times a day. In a week, the pair were fit to return to the farm.”

With the next big storm, the goat farmer anticipated Rio Linda floods. To avoid barn overcrowding, she evacuated some pregnant moms. Their 20-mile drive to Carmichael set more than wheels in motion. The morning after the journey, Friedrich was astonished to find a flock of healthy babies in the home barn.

“Goat moms deliver quietly,” she explains. “They usually have twins. One had triplets. Newborns are cleaned and standing up to feed in 30 minutes.”

Friedrich and husband Tim Blaine established their herd six years ago so their developmentally disabled son Nick could have a meaningful occupation. Their Rio Linda operation also hosts visits from other disabled adults, and produces milk and cheese as a sideline.

Nick is overjoyed with the little leaping additions to the herd, reports his mom. “He loves to cuddle them and help keep them warm,” she says. “Having goats to care for gives our son something extra to love. Goats and their babies take that love willingly.”

BEST BUSINESSES ON THE BALLOT

Best of Carmichael 2019, the annual popularity contest that allows community members to support their favorite merchants and services, is now underway.

Categories include best restaurant, best community center, best event, best senior home and dozens more that make 95608 a commercial hub. Carmichael residency is not required for voters, but businesses must be local or members of the Carmichael Chamber of Commerce.

An awards dinner will be held at the Milagro Centre on Friday, May 31. The event will include a dessert auction with treats donated by local bakeries and restaurants. Admission is $65. For event or sponsorship information, call the chamber at (916) 481-1002.

To vote for your Best of Carmichael choices, visit www.bestofcarmichael.com. Deadline to vote is 5 p.m., Tuesday, May 21.

THE LIFE THAT JACK BUILT

A warrior for nation, God and community, Jack Pefley died recently at 95. Born in 1923 at 12 pounds, 8 ounces, Pefley’s infant moniker, “the wee one,” stuck for life.

He and siblings were country kids during the Great Depression. Community matriarch Mary Deterding was a neighbor. The pioneer children hiked 6 miles to San Juan High School and sang psalms at Carmichael Presbyterian (then Carmichael Community Church). In summer, they ran wild along American River bottomlands.

During World War II, Pefley began a 25-year naval career. He learned to fly amphibious craft from Donner Lake, where the farm boy’s instinctive skill was noted. Called an “absolute artist” in the cockpit, he saw action in the Philippines, Japan and Korea. The pilot later dog-fought with Russian MIGs during the Cold War.

In his Korean deployment, he was hailed for getting war-wounded passengers off a downed PBM Mariner, while “working pedals” to keep the amphibian afloat. He then re-flew and saved the aircraft. Asked how he managed the feat, Pefley replied, “I’m a Carmichael farm boy. I know how to drive a tractor.”

Service continued during peacetime. As a test pilot, he mastered jets and survived three prototype crashes. He and Hatboro native Jerri Kratz married in 1948, raised three kids and last year marked their 70th wedding anniversary. The nonagenarian groom offered marital advice: “be away from home as much as possible,” he joked. Indeed, Navy postings to Japan, Morocco, Philippines and France—and a subsequent civilian airline career—meant many long family separations.

In 1983, the pilot retired to his “Rockin’ KP (Kratz-Pefley) Ranch” and resumed farm chores. Community endeavors included support of the Carmichael Chamber of Commerce and Carmichael Park District, and nine decades of fidelity to his church. He offered a wide smile while laboring (in lederhosen shorts) among grapevines his ancestors planted on Palm Drive. Jack’s quips were legend and—like those of many Greatest Generation survivors—the punchlines were seldom politically correct.

As his health declined, the Pefleys moved to Carmichael’s Eskaton Village and recently to Mercy McMahon Terrace in Sacramento. There, the man of God cheerfully told friends he would soon be in heaven. He left them days after the prophecy.

“Dad’s only complaint was that he would have preferred to die in Carmichael,” says daughter Christine Mayer. “He was a Carmichael boy, through and through.”

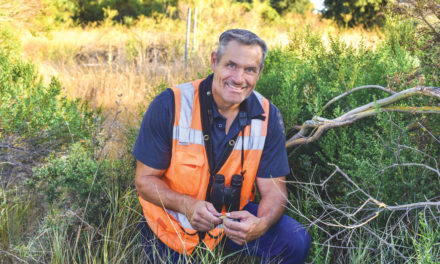

ROTARIAN’S GIFT FOR NATIVE VILLAGE

Carmichael resident Richard Olebe’s baby brother died from drinking contaminated water in Uganda, 67 years ago. Thanks to efforts by Olebe and Rotarians, more than 10,000 Ugandans now rejoice in safe water.

Spearheading the mission, Olebe is well versed in his homeland’s needs. “My sisters spent hours every day collecting dirty water,” he recalls. “As a result, they couldn’t go to school. It’s not just a Ugandan problem—300 million Africans still don’t have access to safe drinking water.”

The Kenya and Stanford-trained engineer worked for the California Department of Water Resources for 22 years. He joined the Carmichael Rotary Club two years ago.

“In 2016, Rotarians from Tororo (Uganda) approached me suggesting a project,” he explains. “They proposed replacing dirty water supplies for my former village of Iyolwa in southeast Uganda.”

A plan to drill wells, dig pipelines and build tanks was approved. Fundraising for the $200,000 effort began last year. Rotarians in Tororo and Carmichael came up with nearly $60,000. This sum was matched by club members in Sacramento, Uganda and Tanzania. Rotary Foundation Global Matching Funds supplied the balance.

“Iyolwa people began drinking water from our wells in December,” Olebe reports.

“These are poor, poor, people,” he says. “I’m proud we could do this for them. They now have safe, free water for the first time in their lives. Babies won’t die like my brother did. Girls will go to school instead of trudging miles with jerry cans. The villagers dug pipelines and will share costs of well and pipeline maintenance.”

Now retired, Olebe self-funded several trips to his homeland as the project progressed. “I’ve seen people’s faces,” he says. “They’re happy and grateful. I’m grateful Carmichael and Tororo could come together like this. Helping a village is one step toward saving the world.”

SEASONAL WORKER TO 36-YEAR CAREER

“It’ll be great to see Garfield House functioning to enrich our cash-poor district,” predicts Carmichael Recreation and Park District visionary Keith Maddison, who retired from his 36-year career last month.

Maddison still hopes to see the improvements he planned for Sutter-Jensen Park. His designs for the redeveloped beauty-spot include turning a 70-year-old former family home into an event center. The rustic Garfield House will be available for private events by fall.

“It’s a beautiful building in a beautiful setting,” Maddison enthuses. “With its surrounding garden, I can’t imagine a better spot for weddings.”

His CRPD job began with seasonal work and in recent years the self-taught tradesman oversaw development of five community parks. The retired park services manager is credited with saving the cash-poor district millions of dollars by thinking outside (and sometimes inside) the box.

“I’ve used district staff in as many projects as possible,” he explains. “We’ve economized by not hiring project managers or general contractors. I’ve filled those roles myself. My Carmichael Park water system plan was approved by our engineers. With help from Carmichael Water District, we saved more than a million dollars in construction. We also cut meter tap fees by $40,000 a year.”

When new Jan Park trails met a ditch, Maddison located an old metal bridge among Sunrise Park District relics. “They gave it to us to renovate,” says the economy guru. “That saved $10,000. When you don’t have money, it’s good to have friends.”

Maddison’s problem-solving genius evolved over a lifetime. “At 14, I built a house with my dad. While enlisted, I worked in a U.S. Navy shipyard. I built mobile homes in Woodland. There’s hardly a challenge I haven’t encountered on building sites. I don’t stand around barking orders. I work from the trenches. I’ve had a fantastic district staff. I couldn’t have managed without them.”

A harder problem to solve is how the father of five will handle retirement. “I started off in a job,” he considers. “It developed into a career and at some point, I took emotional ownership of all our district facilities. I’ll probably come back here and volunteer.”

Susan Maxwell Skinner can be reached at sknrband@aol.com. Submissions are due six weeks prior to the publication month.