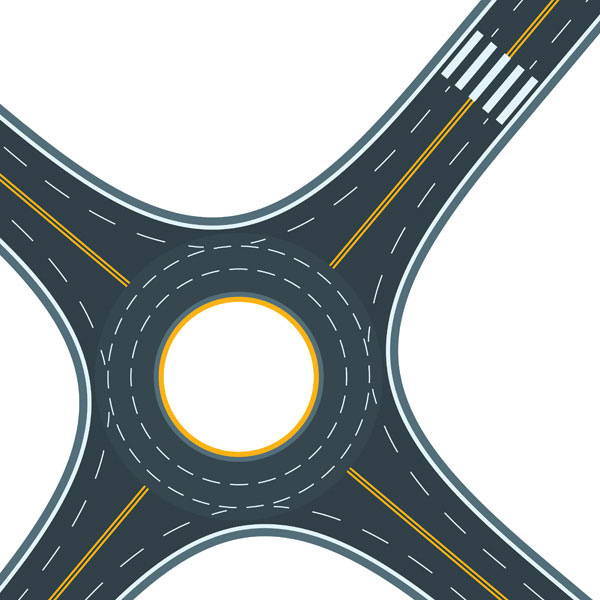

Street intersections are dangerous. Each day, more than 20 people die in intersection collisions in the United States.

Safety is why European nations, Australia and New Zealand turned to roundabouts instead of signals or stop-controlled intersections. With far fewer contact points where vehicles (and pedestrians) cross paths, roundabouts reduce fatal and injury crashes by 80 percent, Federal Highway Administration data show.

Modern roundabouts aren’t the same as Midtown’s small traffic circles, which have stop signs on some approaches. A fundamental difference is that drivers must yield to traffic already in a roundabout.

Roundabouts eliminate T-bone collisions and cause vehicles to slow by deflecting them from straighter paths. If there are collisions, they tend to be sideswipes, not catastrophes calling for an ambulance.

Modern roundabouts use long, raised concrete “splitter islands” in the middle of each approach road to guide traffic to the right. The islands offer a refuge for pedestrians who need to cross only one lane at a time. Paved aprons on the central islands allow large vehicles, such as fire engines and semis, to squeeze through.

Roundabouts can decrease carbon dioxide emissions by up to 59 percent. They reduce traffic delays and operate when power outages darken traffic lights. Roundabouts provide an aesthetic twist and sense of place. Central islands can be landscaped or feature sculptures or fountains.

For decades, federal authorities have encouraged roundabouts. They are supported by AARP, which touts their safety for older drivers and pedestrians. The Insurance Institute for Highway Safety hails their benefits. Roundabouts top AAA’s list of ways to make roads safer.

There are an estimated 7,900 roundabouts in the U.S., a fraction of the 3 million signal intersections. Sacramento has six roundabouts. The county has two, with 508 signal intersections.

Excellent candidates for roundabouts are H Street and Carlson Drive, J and 39th streets, and Elvas Avenue and J Street. A roundabout at Elvas and J might take less space than the current freeway-style interchange.

One exception to the typical U.S. disdain for roundabouts is Carmel, Indiana, a city of 102,000 near Indianapolis. Carmel has 140 roundabouts with seven more planned. Mayor James Brainard is the force behind Carmel’s roundabout revolution.

“Most lanes are needed just to store cars at intersections. We’ve been able to reduce four- or five-lane roads to one lane in each direction because roundabouts can handle 50 percent more cars per hour. That’s a tremendous cost savings for cities,” the mayor tells me.

You’d think cities and counties would be all over themselves building roundabouts. But it hasn’t happened. Traffic engineers are cautious, rightfully so since mistakes can cost lives. But so can lack of action.

The public is resistant to change. Some drivers find a one-lane roundabout confusing. Using a two-lane roundabout is far less intuitive. However, once roundabouts are installed, public resistance uniformly flips to approval. Familiarity and effectiveness make a difference.

Roundabouts can take up a lot of room. Intersections in developed areas may not have big enough footprints. But compact, tightly constructed roundabouts are feasible. Carmel freed up space by reducing lanes and using the room to add bike lanes, trees and wider sidewalks.

Roundabouts can be expensive. Center island landscaping requires maintenance. But traffic signals aren’t cheap. They need electricity and upkeep. Signals have less than half the service life of roundabouts.

Some of the cost savings of roundabouts don’t accrue to the government agency that builds them—so those savings may be overlooked.

Roundabouts save gas (about 26,000 gallons per year per roundabout, Brainard says) and reduce emission levels. They cut insurance outlays. The value of fewer deaths is incalculable.

It’s time for America to accelerate the pace of building roundabouts and decelerate the speed of cars. Going ’round is the way to go.

Walt Seifert is executive director of Sacramento Trailnet, an organization devoted to promoting greenways with paved trails. He can be reached at bikeguy@surewest.net. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram: @insidesacramento.