There was a time when writing about sports meant more than watching games on TV and holding up iPhones at press conferences. Old sportswriters like me sometimes got to hang around with people they wrote about.

My top three hang outs were Jesse Owens, Bill Russell, Willie Mays and Mario Andretti. No introductions needed.

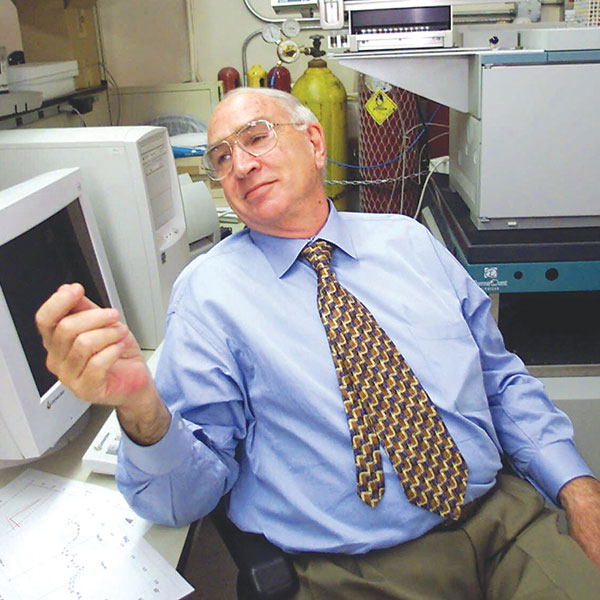

But there was another sports figure who made a big impression. His name was Dr. Donald H. Catlin. The doctor taught me lots about sports and the drive to win at any cost.

Catlin was a plainspoken physician who understood the terrible choices athletes make to win. Many are prepared to destroy themselves. Catlin spent his career trying to prevent these suicidal motivations.

Catlin died this year with dementia at 85. The arrival of the Paris Olympics made me think about his work. I wish he were around to help the Summer Games advance with fair play and sanity. Without him, the Olympics are in trouble.

Today we have the World Anti-Doping Agency, the global authority in testing. The agency’s negligence helped Chinese swimmers cheat at the 2021 Tokyo Olympics. Eleven of those swimmers are in Paris.

I got to know Catlin in the 1980s, when his UCLA lab became the world’s barrier against performance-enhancement drugs. The lab tested athletes at the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics.

Records are imprecise, but Catlin disqualified between nine and 18 Olympians. The Soviet Union boycotted L.A., no doubt lowering the numbers.

Catlin’s main targets were anabolic steroids. Eventually, the cheater’s pharmacy included compounds harder to detect and sophisticated in their impact.

I met Catlin several times. There was a brief interview at an NCAA convention in San Diego. Next came an invitation to his UCLA testing lab. He journeyed to Sacramento for several speeches.

One evening found the doctor at The Ram restaurant on Watt Avenue, where he addressed the Sacramento Section of the American Chemical Society.

At his UCLA lab, Catlin described the eternal nature of his pursuit. He said, “They’re always coming up with ways to mask performance-enhancing substances to fool the test. But we stay one step ahead.”

Before meeting Catlin, I didn’t think much about the problem of athletes using chemicals to improve strength, speed and endurance. Drugs and sports were best friends.

Baseball players went to work drunk in the early 20th century. Football players in the 1960s swallowed handfuls of painkillers. Visit many pro locker rooms in the 1970s and find cigarette butts and empty beer cans.

Catlin explained the distinction between old-school narcotics, booze and steroids. Playing drunk is dangerous. Steroids and various performance enhancements destroy athletic integrity. They force everybody to cheat.

He told me, “If the person you compete against takes enhancement drugs, you’ve got a choice to make. Either you start taking similar drugs, or you lose your job. You can’t compete against it.”

He was talking about high school kids but could have meant athletes in Paris going against Chinese swimmers. Beyond disrupting fair play, drugs impose serious health consequences. Catlin’s tests helped guarantee clean, honest games.

Then and now, coaches were a problem. Coaches play dumb, but they know when athletes use performance enhancements. Muscles, speed and attitude change in telltale ways. Catlin exposed what coaches try to hide.

Around the time I met Catlin, my newspaper published a series of stories on the scourge of drugs in local sports.

We talked to Dave Hotell, football coach at Sacramento High School. Like many coaches who began careers in the 1950s, Hotell was more worried about whiskey and cannabis than steroids.

When he confronted suspected teenage drug users, Hotell struggled to believe his athletes needed any more stimulation than pure competition.

He said, “If they admit to being on something, I thank them for being man enough to admit it and then clean out their locker. I just don’t understand it. I get 30-feet high when they’re playing the national anthem.”

R.E. Graswich can be reached at regraswich@icloud.com. Follow us on Facebook and Instagram: @insidesacramento.