Earlier this year, when kick boxing ate pro wrestling for breakfast, I wondered what Red Bastien would make of the meal.

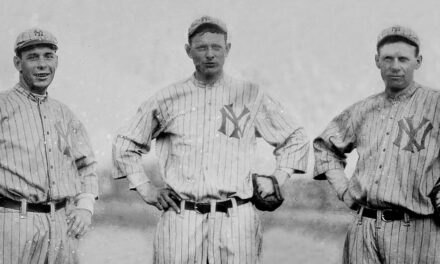

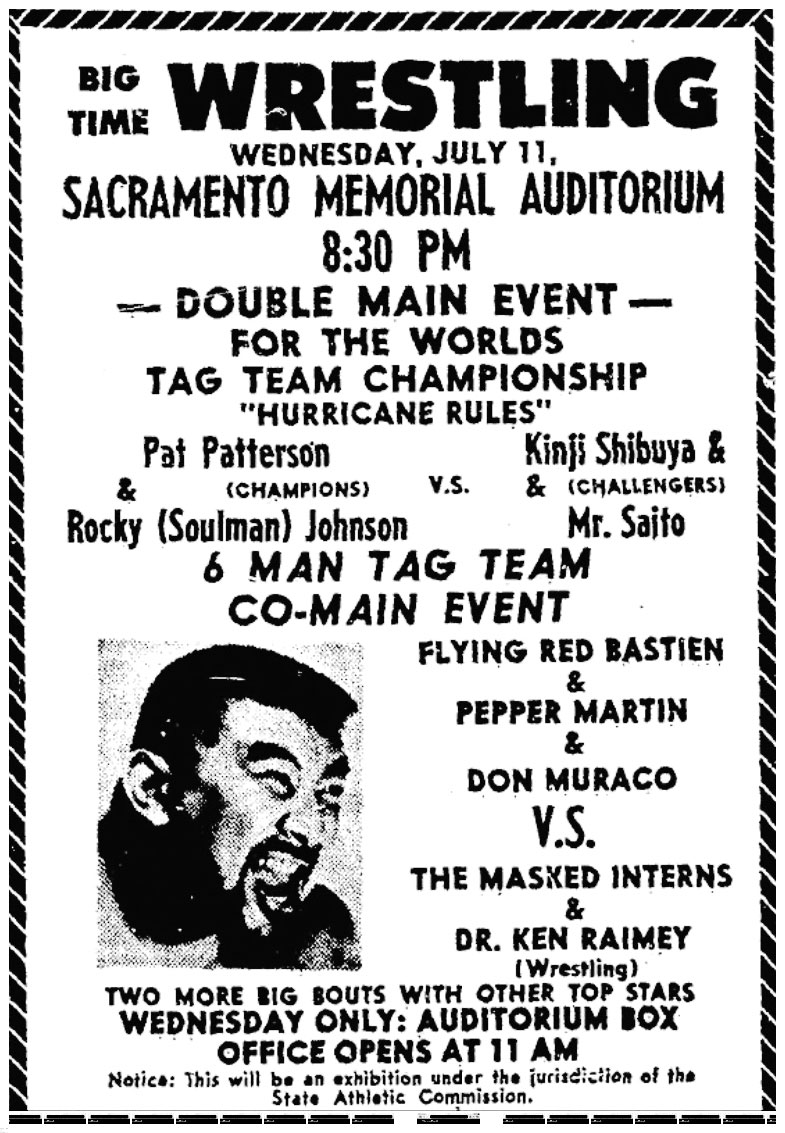

Bastien was the last promoter to book monthly wrestling shows at Memorial Auditorium. He was also a champion pro wrestler. He could hold his own against Rocky “Soulman” Johnson, Kinji Shibuya, Pepper Martin and Pat Patterson, but not all at once.

Pro wrestling was a weekly, biweekly or monthly attraction at Memorial Auditorium since before World War II. The mayhem ended in 1986, when the building closed for 10 years while authorities contemplated seismic repairs.

New promoters tried to revive Memorial Auditorium as a pro wrestling cathedral in 1997–1998 with five shows called “Superstars of Wrestling.” The ring shook with thunderous leaps from the steel turnbuckles. Seats stayed mostly empty. Blame Vince McMahon.

McMahon flattened the profitability of local wrestling in the late 1980s, when he built the World Wrestling Federation into a cable TV monster. McMahon hired the game’s biggest stars. He bulldozed local traditions like the one at 15th and J streets.

I thought about those old shows when I learned McMahon was finally swallowed by a smarter, younger promoter, Ari Emanuel, a Hollywood agent. Emanuel bought McMahon’s wrestling operation and combined it with the mixed martial arts Ultimate Fighting Championship. The marriage produced a $21 billion machine of staged TV brutality.

Red Bastien, who died in 2012 at age 81, would be impressed by Emanuel’s ambition. As a 48-year-old pro wrestler turned Sacramento promoter, Red complained about paying $1,000 rent at Memorial Auditorium. The steep overhead left him with crumbs.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Bastien, Pepper Gomez, the Masked Interns, Dr. Ken Raimey and many others grappled their way through town. They choreographed their matches under rules of “kayfabe,” carnival slang for theatrics carried to the edge of plausibility, at least in the audience’s mind.

Here was kayfabe: battle royals ending with an elbow smash, atomic drop or Boston crab. Heels and faces, villains and good guys. Top showmen known as workers. Workers threw good bumps. They launched opponents skyward. Spectacular climaxes were called finishes. Once finished, workers, faces and heels, showered fast, iced their bumps and carpooled to Stockton.

Bastien swore he could still wrestle when he became a promoter in 1979. His body disagreed. His decline began four years earlier when he was blindsided by Vern Stevens during ring introductions at Memorial Auditorium.

Sneak assaults were not unknown in pro wrestling, but this one hurt. Stevens didn’t realize Bastien was in pain from a weight-lifting injury. Red tried to defend himself, but couldn’t move. He was hauled from the canvas on a stretcher.

Pro wrestling was territorial. Promoters carved up geographic swaths and avoided competing against each other. Sacramento was serviced by two Northern California promoters, Roy Shire and Louie Miller.

In the late 1970s, Shire and Miller feuded. The partners became competitors. Bastien saw an opportunity at Memorial Auditorium. He booked two shows a month, Wednesdays at 8:30 p.m., wrestling time.

The Shire and Miller battle ignited over a bear. As deranged as this sounds today, bears sometimes joined wrestling shows 50 years ago at Memorial Auditorium. They were audience favorites. They often subdued their human opponents.

In 1974, Victor the Wrestling Bear was booked into Memorial Auditorium by Shire and Miller. Thousands of tickets were sold. Full house! But hours before showtime, Shire and Victor’s owner argued over payment.

The owner refused to produce the bear.

Shire panicked. He ordered ring announcer Hank Renner to tell the crowd Victor was killed in a car crash traveling from Arizona to Sacramento.

Miller sued Shire. The plaintiff alleged the defendant’s bear fiasco ruined wrestling’s local reputation. Bastien tried rebuilding that reputation, but the damage was done.

I can’t find the judicial outcome of Miller v. Shire. But I know three facts about Victor.

First, she was not male as advertised. Second, Victor was not her real name. Third, she was not killed in a car crash in 1974.

She wrestled in Oakland as recently as 1978, under an alias. I want to say she won.

R.E. Graswich can be reached at regraswich@icloud.com. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram: @insidesacramento.