Coming to America

The immigrant experience defines us

By Cecily Hastings

July 2018

The American experience is by and large the immigrant experience. Millions of people from all over the world have come to our great nation in order to find opportunity and freedom and to pursue happiness. Those last two things are unique to America. Our founders enshrined the phrase “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness” in the Declaration of Independence.

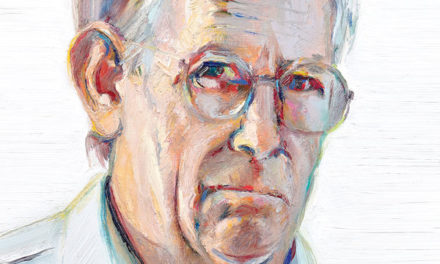

A few months ago, I was honored to receive a dinner invitation from Dr. Robert Nelsen, the president of Sacramento State University. He also invited the university’s provost, Dr. Ching-Hua Wang, who had been on the job about a year. Over Mexican food at the new Zocalo off Fair Oaks Boulevard, Nelsen shared Wang’s amazing immigrant story with me. When I couldn’t get enough of the great story, Wang filled in the details.

As provost (the university’s second-highest position), Wang oversees the Office of Academic Affairs. It’s the largest unit on campus and includes the university’s seven academic colleges, the library and the continuing-education college.

Before coming to Sac State, Wang served as the dean of the School of Health and Natural Sciences at Dominican University of California. There, she was also a professor of immunology and microbiology, and she managed all extramural grants for the school. Before that, Wang was one of 13 founding faculty members at CSU Channel Islands.

“While at Channel Islands, I led the development and implementation of eight science and health science programs and worked closely with colleagues in starting, advancing and growing the university,” said Wang.

She was born in Beijing, the oldest of four children. “While growing up, I experienced one of the darkest periods of Chinese history,” she told me. “I witnessed tremendous turmoil and devastating hardships. My family was split into pieces, and I was sent to Inner Mongolia to get ‘re-educated.’

“When I was living in Inner Mongolia, I served as an elementary teacher at a one-

room schoolhouse. My interactions with students from extremely poor families left an indelible impression on me.”

In China, Wang earned a master’s degree in immunology and a medical degree. In the winter of 1981, she came to Ithaca, N.Y., to get her Ph.D. in immunology at Cornell University. “I had been so isolated and had no idea what Americans dressed like,” she recalled. “Before I left, I found a pair of bell-bottoms and thought I’d fit in. But it turned out that fashion trend had long passed!

“Both my suitcase handles broke because—rather than bringing clothes—I dragged along all my treasured books. I only had two $10 bills to my name—the maximum amount of cash the Chinese government would let us exchange. And I spent one of the bills to tip a porter who helped me with a cart for my suitcases at the airport.”

While living in the United States, Wang and her husband, Nian-Sheng Huang (a historian and published author who specializes in Early American history), had two children. The couple held green cards and remained Chinese citizens until the Tiananmen Square massacre in Beijing in 1989. “With thousands being murdered for expressing their desires for freedom, we knew for certain that we’d never return there with our children,” Wang said.

In 1990, they moved to California to work in the California State University system. They wanted “to teach students who are mostly first-generation college students and come from humble backgrounds,” Wang said. “People just like us.” After moving to California, Wang and her husband became proud U.S. citizens.

Her favorite thing about this country? “Freedom!” she said enthusiastically. “I will never forget the amazing sense of disbelief that I felt when I first walked free on the campus of Cornell. I had never known anything like it. There were so many choices and so many opportunities!

“Later on, I had the joy of learning about the history of our country and the millions of U.S citizens who gave their lives for freedom—not just of our own citizens, but to literally save the world from tyranny.

“To this day, I am still filled with an overwhelming sense of gratitude for what our country provides to both our citizens and the entire world. It left me with a desire to give back for what was given to me. That will remain my pledge as long as I am alive.”

After we finished dinner, Nelson turned to me, smiled and said, “I guess you have already figured out why I wanted this woman as a leader on our campus. She totally understands what many of our students are going through.”

Here at Inside Publications, one of our loveliest employees is photographer Linda Smolek, who was born and raised in Malmo, Sweden. We hired her after she graduated from Sac State, where she earned a double major in photography and communications—an education that she fully funded herself.

After high school, Linda, an only child, stunned her parents by making all her own arrangements to attend Sac State as an international student. Arriving on her own at Sacramento International Airport, she took a taxi to her dorm room.

In her freshman year, she met and fell in love with Jay Gerkovich, who later became her husband. They now have two children, who speak both English sand Swedish. I asked her recently why she became a U.S citizen in 2013, after more than a decade as a green-card holder. “I wanted a voice in our country’s governance. I wanted to vote and be a part of decision making in our country,” she said.

Her mother is Swedish, her father Croatian. “I had already dealt with the immigrant experience growing up in Sweden, which is a very homogeneous country,” she said. “In fact, the only discrimination I ever felt in my life was growing up in Sweden as the child of an immigrant father. Nothing like that has ever remotely happened to me in America.”

As you celebrate a joyous Fourth of July this month, please remember these two immigrant stories and the simple statement “Freedom Is Not Free” engraved into one wall at the Korean War Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C.

Cecily Hastings can be reached at publisher@insidepublications.com.