He Puts Water To Work

This hydroponic farmer grows tender greens without soil

By Angela Knight

May 2018

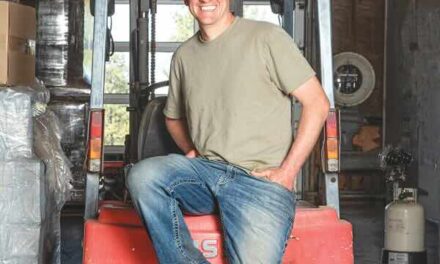

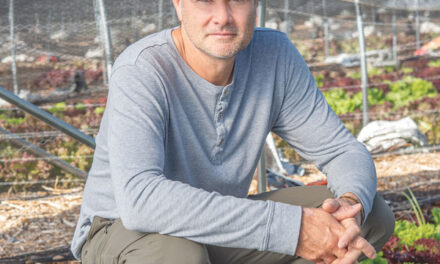

I’m inside a shipping container located in a residential neighborhood. On both sides of the aisle, rows and rows of tender plants—heads of lettuce, herbs and microgreens—grow in trays. They bask under energy-efficient LED lights, which bathe everything in a red-tinged glow. A thin film of water flows past the plants’ roots, providing nutrients, while fans circulate the air. Jason Levens, 36, the founder of Aldon’s Leafy Greens, spends a lot of time in this engineered environment, tending his hydroponically grown charges, but he loves the work. “Every single plant in here I’ve seeded,” he says.

When I Google “hydroponics,” I discover it comes from the Greek words for water and work: water working. It is a way to grow plants in water, without soil.

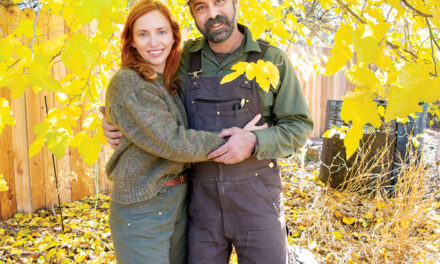

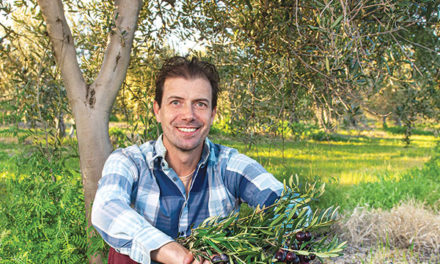

Levens and his wife, Sophia, purchased property in Fair Oaks, called Urban Art Farm, more than a year and a half ago. Along with the shipping container and a cottage, it supports 22 olive trees and various pieces of outdoor art. They live in a modern home on the property, which was designed by Sage Architecture for the original owners. A gallery space runs through the middle of the house, but the walls are a blank slate. The couple’s young son, Aldon, uses the hallway like a track.

A large red yo-yo hangs from a tree in the backyard. It belonged to the previous owners, but the Levenses wanted to keep it. A flock of chickens, as well as a collection of red wigglers (Levens is also into vermiculture, a method of decomposing organic waste using worms), reside nearby. Next year, Levens wants to start an annual canning party to preserve the olives from their trees. He also plans to develop a soil-based garden to grow edible flowers as well as different kinds of vegetables for his family. For now, the company’s edible flowers are grown off-site.

Before they moved to Fair Oaks, he and his wife were living in a tiny apartment in Noe Valley. That shipping container is miles from San Francisco and Levens’ “corporate job” at Shaw Industries; he gave up city life and a sales career to move back home and start an urban-agriculture business. “I got tired of the whole corporate market,” he says. He grew up in Folsom and attended Fair Oaks Elementary School. He’s pursuing a degree in applied horticulture, and he’s working on becoming a master gardener. In the future, he wants to be a consultant for other indoor growers.

A taste test revealed that I’d likely fail at identifying greens. To my embarrassment, carrot tasted like celery to me, but thankfully pea shoots looked and tasted like peas; nasturtium shoots were strong tasting, as you might imagine, so Levens saved them for last. I savored too many varieties to keep track, and I was busy chewing, but some stood out: red-veined sorrel and romaine, wasabi and daikon radish. Everything was crisp and fresh and red, under the lights, and I pictured the microgreens topping everything from sushi to dessert. Levens says he can identify the plants he grows based on taste and can identify the seeds by sight. Local chefs occasionally drop by the shipping container to sample product. I’m sure they could pass the taste test.

The budding business means a lot to Levens. “It’s my baby,” he says. He brushes his hand across the microgreens, as if smoothing a young child’s hair. This Renaissance man grows 25 or so varieties of microgreens, four or five varieties of lettuce and about 10 herbs in that engineered space, using nutrient film technique, or NFT.

Here’s a simplified explanation of NFT: The plant roots absorb necessary nutrients from a thin film of water, which is circulated by pumps. Microgreens are grown on what Levens calls “baby blankets,” or organic fibers, while lettuce is nestled in rock wool—a growing medium. According to the company’s website, Levens uses products approved by OMRI, the Organic Materials Review Institute. And he’s picky about his greens. “I feed my son this,” he says.

The system can be controlled from a control panel or Levens’ iPhone. He changes the water every month, but contrary to the hydro part of the word, hydroponics uses very little of the stuff. Levens’ father, company co-founder Mark Levens, estimates the shipping container can yield the same amount of produce as an acre of land over a year. It’s also cool in the summer, which is an advantage. Other potential advantages? A sterile environment with no pesticides, herbicides or GMOs; the ability to grow greens year-round; it uses less space and less water than traditional soil-based gardening; and there are no weeds. Potential disadvantages? It’s expensive to set up; it requires constant monitoring; there can be a huge learning curve.

You can taste Aldon’s greens at local restaurants, including Mulvaney’s B&L, Kru, Mother and Localis, and purchase them at Taylor’s Market in Land Park.

Angela Knight can be reached at knight@mcn.org.