Hop Harvest

Local Brewer Learns Hop Farming Firsthand

By Daniel Barnes

October 2018

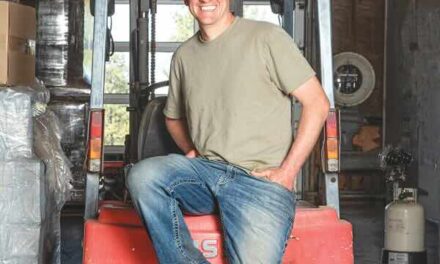

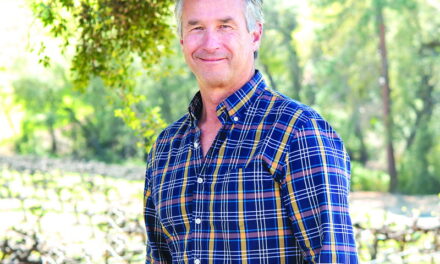

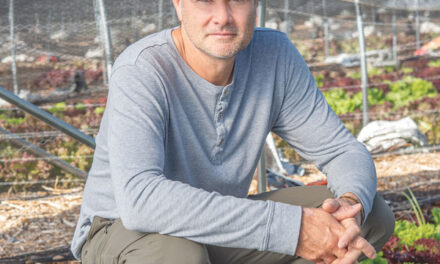

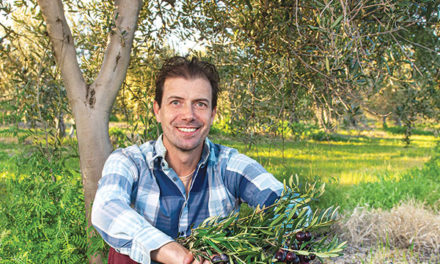

August is harvest time in the hop fields of California, so Rohit Nayyar has left the air-conditioned comfort of his RoCo Taproom & Bottleshop in West Sacramento to brave the sweltering Yuba City heat. “During the hops season, it’s all hands on deck,” says Nayyar, who is more known for selling and pouring beers than for harvesting their raw ingredients. However, growing hops has also increased Nayyar’s appreciation of how they eventually get used by brewers. “You’ll understand how many hours go into growing these hops, just to get the one pint of beer.”

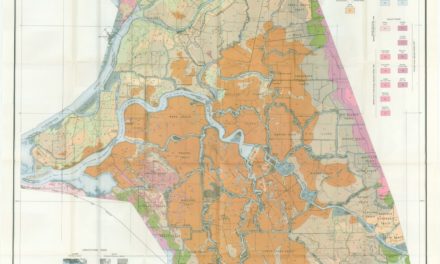

Nayyar’s nascent farming career started six years ago when his friend Julien Lux, owner of New Glory Craft Brewery in Sacramento, gave him the idea. California once had a rich history of hop farming, but now the industry is almost entirely centered in Oregon and Washington.

“There used to be a lot of hops grown here, but that went away because a lot of the processing wasn’t here, and nobody was using whole cone hops, everybody started pelletizing them,” Nayyar says. “California lacks the equipment and the infrastructure for hops growing and processing.”

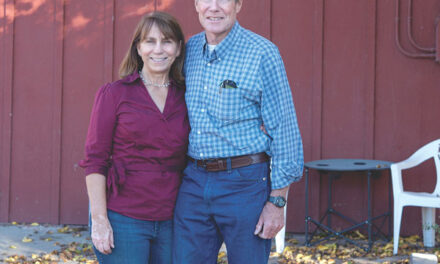

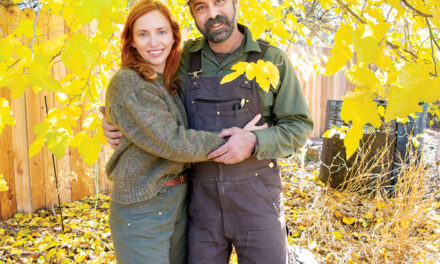

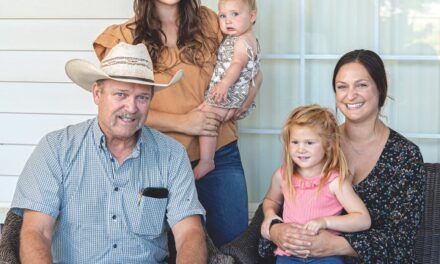

Nayyar reached out to his best friend, Jaspaul Banes, and the two men decided to become partners in the hop business. They found a piece of land in Yuba City where they could grow hops. “We planted an acre of hops just to see how it goes,” Nayyar says. “From there, we got such a good response and kept on growing more and more, and now we have two different hop growers that grow for us, and we grew our acreage up to almost 15 acres.”

The enthusiastic duo handpicked their own hops when they first started growing, but that proved too labor-intensive, so they invested in a small harvester. With each bine producing nearly 5 pounds of hop flowers, it would take several hours to handpick a single bine. They only grow non-proprietary hop varieties like Cascade, CTZ, Chinook, Magnum, California Cluster and Nayyar’s favorite varietal, Centennial. “It used to be one of the popular hops, it was a proprietary hop at one point,” Nayyar says. “It became the main hop in every West Coast IPA.”

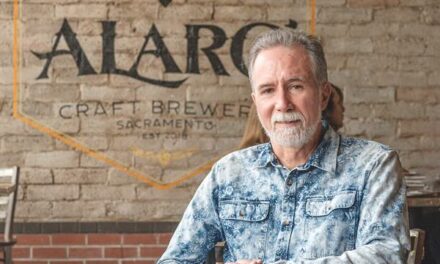

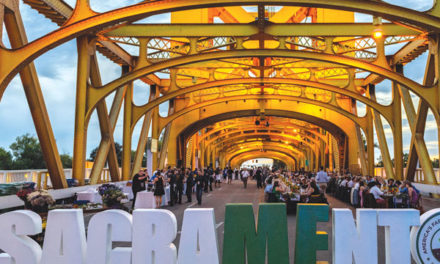

Since the hop harvest happens in late summer, early autumn is the time for “fresh hop” (or “wet hop”) beers. These beers are brewed with freshly picked, whole cone hop flowers instead of the concentrated hop pellets that most brewers use year-round. “The local breweries like New Glory, Knee Deep and Jackrabbit, they supported us,” Nayyar says. “In the beginning, it was just those three breweries, but now we’re serving close to 80 different breweries all around Northern California.”

Before 2018, Nayyar’s hop farms only produced enough to supply local brewers during fresh hop beer season, but this will be the first year that they produce enough hops to sell throughout the year. Any hop flowers left on the bine after the August harvest will eventually get picked and pelletized. “We finally are in a position where we have enough hops to sell all year long instead of having to rush off to market.”

One of the most widely distributed wet hop beers made with Nayyar’s hops is Wobblies Wet Hop Ale by Calicraft Brewing Co. of Walnut Creek. However, the one that sticks out to Nayyar is an annual beer made by West Sacramento brewery Jackrabbit Brewing Co. that uses both fresh hops and fresh peaches from the Yuba City farm. “It’s a nice West Coast-style IPA with all locally sourced ingredients,” he says. “We asked those guys to make that one every year, and they do.”

For all the rewards that Nayyar finds in hop farming, there are still challenges that come with a being a small-scale hop farmer in California. Their hops are more expensive than the ones grown on industrial farms in Oregon and Washington, where most of the processing equipment is located. “If you go to banks to get a loan in California, they’re not used to this kind of a crop and they don’t have data on it,” he says. “We’re spending our money, our own life savings, our own time to grow these hops.”

Instead of adding more acreage for next year’s harvest, Nayyar and Banes plan to make investments in their infrastructure, such as buying a bulk harvester and having it shipped here from Europe. “Big farmers out of Oregon and Washington, they don’t even use a bulk harvester,” says Nayyar. “They have multimillion-dollar facilities built on their farms.

“We’re not there yet, but eventually that’s where we want to get to.”

Daniel Barnes can be reached at danielbarnes@hotmail.com