Ride-hail companies Uber and Lyft have successfully provided their services to millions of customers. The companies are valued in the billions of dollars. Ride hail has been a distinctly disruptive technology in a stodgy transportation world that has seen little real change for decades. Admittedly, the degree of disruption has to be put in context—the overwhelming majority of trips in the U.S. are still made by solo drivers in their own vehicles.

If Uber and Lyft didn’t exist, ride-hail customers presumably would have made their trips by taxi, walking, biking, transit, ambulance (yes, people are choosing Uber over EMTs) or driving. Recent studies show a correlation between the loss of transit ridership and the rise of ride hail.

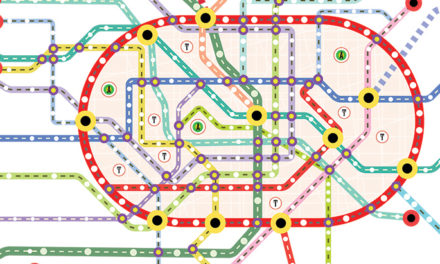

University of Kentucky researchers looked at factors determining transit ridership in 22 major U.S. cities between 2002 and 2018. They discovered that each year after a ride-hail company entered a market, heavy rail ridership decreased 1.29 percent and bus ridership declined by 1.7 percent.

Further, “This (ride hail) effect builds with each passing year and may be an important driver of recent ridership declines,” the researchers said. Their analysis showed other factors, such as changes in service levels, gas prices and auto ownership, didn’t fully explain the decline in transit ridership.

Correlation isn’t causation. But it’s not a great leap of imagination to believe that Uber and Lyft are stealing riders from public transit and inexorably reducing transit ridership.

Locally, Sacramento Regional Transit ridership was down 4.6 percent in 2018, to 20,562,180. In 2014, total annual ridership was nearly 28,000,000. The numbers show RT’s slide has been substantial and persistent.

Uber started Sacramento service in 2013. The initial service, designed around using “black car” limos more efficiently, morphed into what we know today: drivers using their own cars to chauffer customers.

To the extent that ride hail has taken rides from what would have been car trips, it’s generally been a wash for society. One car trip substituted for another doesn’t really make a difference.

But trips taken from walking, biking and transit mean more traffic, more congestion and more harm to the environment. Fewer people get healthy physical activity. Transit systems suffer a loss of revenue, making it harder to provide the same coverage and service frequency. Those are all social negatives.

Despite its popularity, ride hail has not proven its long-term viability. Uber and Lyft have not been profitable. They’ve burned through wads of investors’ cash. They rely on cheap labor by tapping into the gig economy while providing no benefits to their drivers, who are considered independent contractors.

Several studies indicate Uber and Lyft driver net incomes are below minimum wage levels. The MIT Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research concluded that Uber and Lyft drivers make a median $8.55 to $10 per hour, and that 8 percent of drivers lose money. Uber and Lyft and others dispute those figures.

Both Uber and Lyft, currently privately held, plan to sell public stock this year to raise more capital from optimistic and eager new investors. Potential investors foresee the companies and themselves making buckets of money.

Uber and Lyft could get pressured from new shareholders to raise prices in order to turn a profit. As public companies, they would have even more incentive to accelerate development of self-driving technology to eliminate their biggest cost—the dollars that go to drivers.

Uber and Lyft’s current popularity may not be the best thing for everybody in the long run. Their unbridled and continued rapid growth may turn out to be more of a bane than a boon.

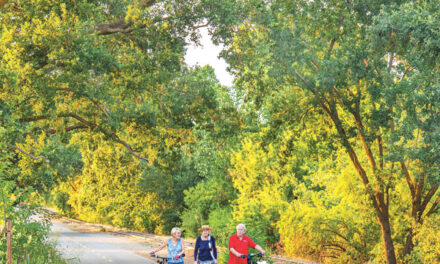

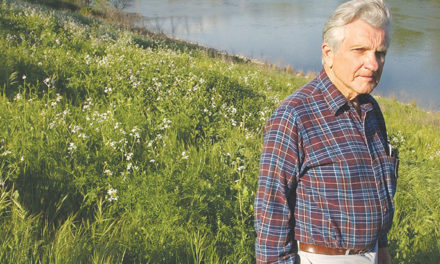

Walt Seifert is executive director of Sacramento Trailnet, an organization devoted to promoting greenways with paved trails. He can be reached at bikeguy@surewest.net