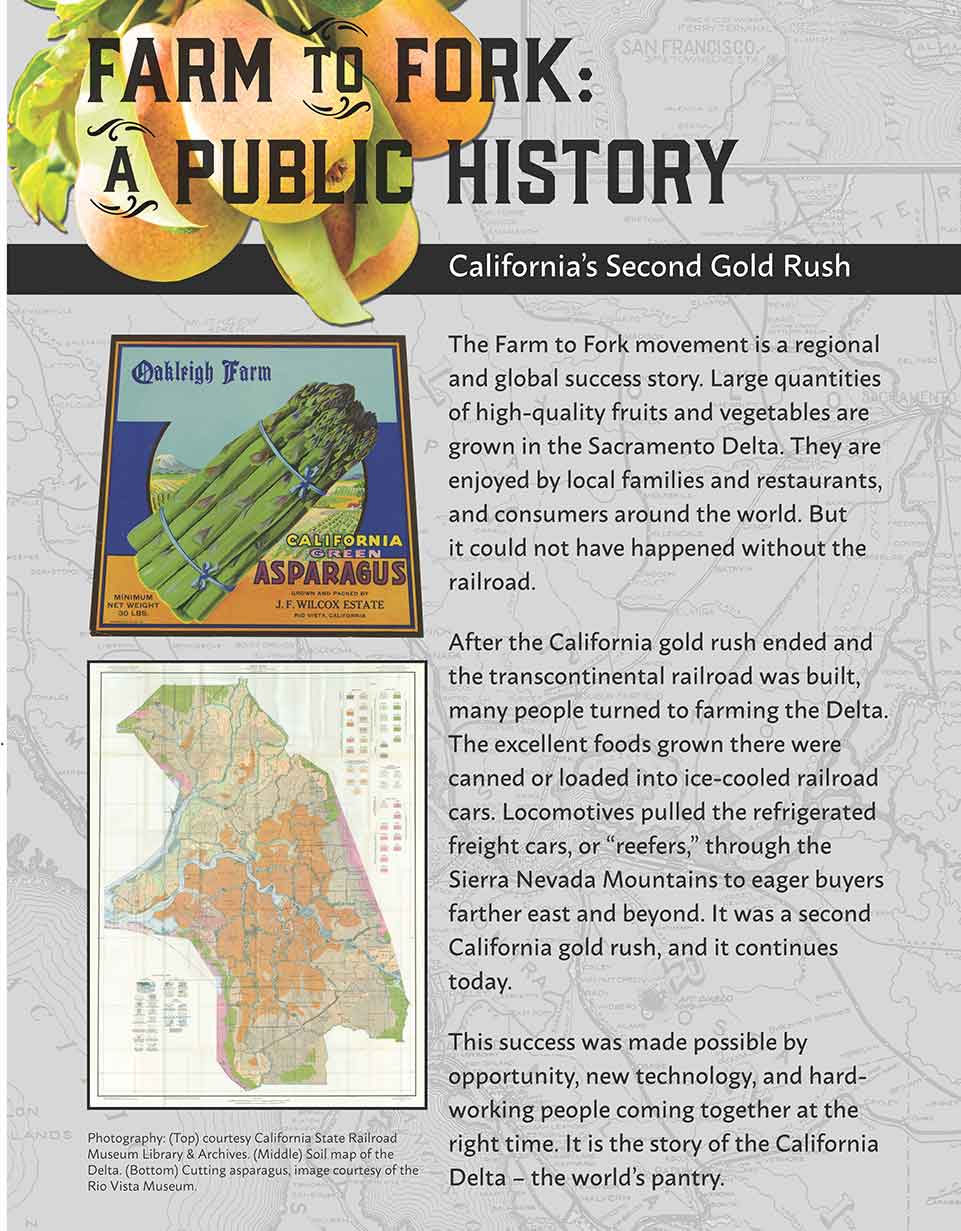

Second Gold Rush

New exhibit tells how the railroad brought California agriculture to the nation

By Steph Rodriguez

June 2019

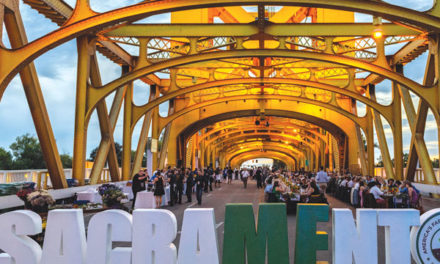

When the water tower off of Interstate 5 changed its trademark to “America’s Farm-to-Fork Capital” in 2017, replacing its longstanding “City of Trees” identity, it stirred debate among many Sacramentans. Was this just another attempt at rebranding the city at a time when mega arenas such as the Golden 1 Center were underway, which might propel Sacramento into a true destination for tourists?

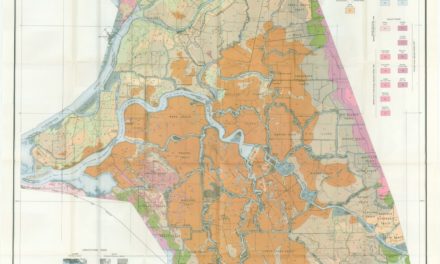

While some residents would dig in their heels and breathe a definitive “yes,” others, namely historians, point to the city’s past. In fact, Sacramento has a long history that’s rich in agriculture and, even in the late 1800s, was booming with ripe pears and asparagus, and acres of walnut and orange groves. The city also was the No. 1 producer of ice, which helped distribute our homegrown produce east, enticing the world to visit sunny California, a land of unimaginable bounty.

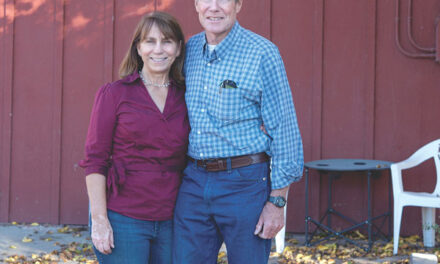

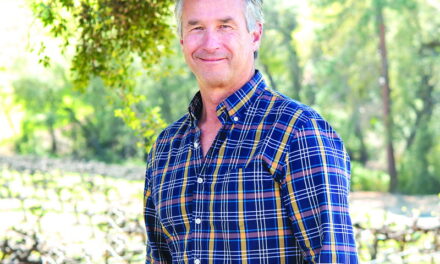

The California State Railroad Museum enjoyed its sesquicentennial anniversary last month, celebrating the joining of the transcontinental railroad on May 10, 1869. The railroads connected in Utah, but it all started right here in Sacramento, says museum director Ty Smith, who also teaches public history part-time at Sacramento State University.

“One thing about railroad history is it’s a diverse history. It ran through every culture: Mexican-American track workers, Mexican track workers, Chinese immigrants, African-American porters. You don’t have to poke around very far before it all starts bubbling up,” Smith says.

Before the transcontinental railroad was completed, the California Gold Rush hit in 1848 where gold fever brought hundreds of thousands of people from all cultures to California in search of riches. But, Smith says, the Gold Rush was a mere “flash in the pan” in terms of Northern California history.

“Our other piece of local history, that’s also world history, is the second Gold Rush, which is the agricultural production of California,” Smith says. “We’re at ground zero for where everything came to be distributed to the rest of the nation. It is really that story of how California and how this region impacted the world.”

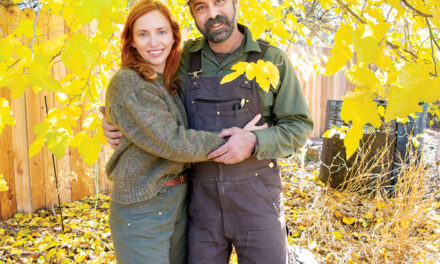

That world impact inspired his public history class at Sacramento State. Together, 16 graduate students were given an assignment: Build an exhibit inside the museum that revives a part of California history involving the railroad.

“They came over here to this refrigerator car and they asked, ‘What is this all about?’” Smith says, pointing to the old rust-colored vessel that sits inside the museum.

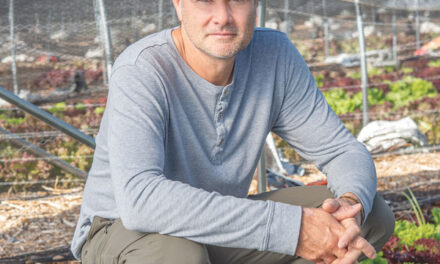

From there, the budding historians posed the question: “How did the farm get to the fork?” The answer: The train. The students spent their 16-week semester as storytellers bringing the deep history to life and giving context to the slogan “farm-to-fork” that now brands Sacramento.

Students did all the archival research and culling of photographs to bring the human history to life. They put in months of research to support their vision until “Farm-to-Fork: A Public History” came to fruition through graphic illustrations, informative slides, black-and-white photography and mannequins posed chucking ice into the historic refrigerator car and selling the colorful bounty of Sacramento and the Delta at local farmers markets.

“Every year, we exported more wealth from this state than we ever found in gold. It just happens to be the gold that grows on trees and in the fields,” Smith says. “And it was Chinese laborers and Mexican-American laborers who worked that land in the Delta and packed stuff up on refrigerator cars and it came right through Sacramento for distribution for the rest of the world.”

At first, “Farm-to-Fork: A Public History” was going to be temporary. But the students’ efforts truly connected museumgoers to the past through the various mediums displayed throughout the exhibit. Smith says the students wanted to give people a vast understanding for their past so they can navigate through their future right here in Sacramento. Because of this, “Farm-to-Fork: A Public History” is now a permanent fixture of the museum with plans to adapt with the changing times as the agricultural movement continues to propel forward.

Farm-to-fork “is not just a dinner on the bridge. It’s really part of our DNA,” Smith says. “Railroad history is all a part of that and connecting what’s going on. It’s very deep. And it runs across cultures.”

Visit “Farm-to-Fork: A Public History” at the California State Railroad Museum in Old Sacramento, open daily from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. For more information, go to www.californiarailroad.museum.

Steph Rodriguez can be reached at wordstospill@gmail.com.