It sounds like common sense: Small buses that provide on-demand service to neighborhoods should be cheap to operate and responsive to residents.

These mini-shuttles, in the past called “dial-a-ride,” now use updated technology, such as smartphone apps and routing by computer algorithm. The technology has given rise to a new term: microtransit.

What could be more appealing than door-to-door service, when you want it, at an affordable price? Microtransit might not have the privacy of an Uber or Lyft ride, but ideally it would be nearly as convenient at considerably less cost.

Public transit consultant Jarrett Walker asserts microtransit is a hollow promise, at least for the non-automated present. In a pointed critique of microtransit in The Atlantic, the Portland, Ore.-based expert says it simply cannot be efficient. The key issues are labor costs and boardings per hour (the rate of passenger pickups).

Labor accounts for 70 percent of the cost of operating passenger transports. That’s why transit agencies own and run the biggest bus they need during a shift. Little buses save little money.

Walker cites an Eno Center for Transportation report about microtransit in several cities. In no city did boardings exceed four an hour. The reason: Buses have to navigate less dense neighborhoods and drivers have to wait while customers gather their possessions. Kansas City ended its yearlong pilot microtransit program with costs reaching roughly an astonishing $1,000 per ride.

While microtransit may be a mix of Uber and transit, we have to remember that Uber is able to provide its taxi-like service at a lower cost by not owning the vehicles nor having drivers who are employees. Usually door-to-door service comes at a much higher cost. A local example is Sacramento Paratransit. In 2008, trips in assistance to disabled people cost $43.52 each.

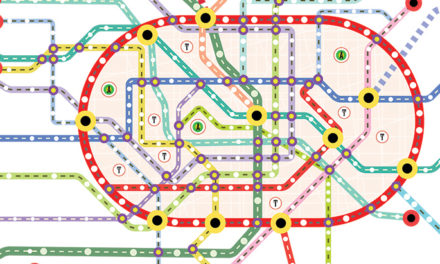

With fixed-route systems, customers gather at stops mostly by walking. Buses can travel straighter direct routes while picking up many more passengers than possible with more customized and circuitous microtransit.

Walker says, “The best way to get the most people around a city efficiently and cheaply isn’t nearly as sexy or high-tech (as microtransit): It’s fixed-route buses.” He adds, “walking is the key to it.”

He continues, “The microtransit promise of ‘service to your door’ is a promise to abolish walking, and yet walking is the essence of how people share precious space.”

For that reason, some microtransit systems don’t provide all pickups at the door and ask riders to walk a bit to designated points.

West Sacramento has started a pilot microtransit program in partnership with the Via rideshare company. You can use a smartphone app (or call if you don’t have a smartphone) to schedule a ride anywhere in the city. A Mercedes van will pick you up “in just minutes.” The cost is $3.50 for a one-way trip and half that for seniors and those with disabilities.

Sacramento Regional Transit offers its pilot SmaRT Rides services around Citrus Heights (including to Kaiser Roseville and the Historic Folsom light rail station) and in the Franklin/South Sacramento area. Small “neighborhood friendly buses” seating 12–14 passengers are used.

When you make your service request via app, by calling or going online, you’ll receive an estimated pickup time. Pickup and drop-off locations must be in the defined service area. Costs are $2.50 per trip or $1.25 for seniors and the disabled, and $1.35 for students in high school or younger. Groups of five or more can travel free if they have the same origin and destination.

The service area coverage that microtransit provides comes at the expense of more frequent trips and higher ridership in places where lots of people will ride. Finding the balance between coverage and ridership is a tricky task that every transit provider has to ponder.

Walker sums up by saying, “If cities want to move people faster than walking while allowing them to take up only their fair share of space, two options arise. One is to use a vehicle that’s not much bigger than the human body, such as bicycles and scooters. Those tools work well for certain people in particular circumstances, but not for everyone.

“The other option is to share the ride in a vehicle. If space is really scarce, that vehicle will have to carry lots of people. In most cases, riders will have to share a vehicle with strangers, people who are not traveling for the same purposes or even to the same places. That’s what public transit is.”

NOTE:

Chariot Loses Race

The end of the road for Chariot proves it’s not easy to make money providing microtransit services.

Chariot announced it would cease operations Feb. 1, keeping some employer-based services alive for another month. San Francisco-based Chariot operated in the Bay Area and in relatively densely populated cities, including Chicago, Denver, Detroit and London.

Two other microtransit providers, Leap Transit and Bridj, previously stopped shuttle services. Leap folded after three months in 2015. Bridj ended American operations in 2017, but still runs in Sydney, Australia.

Chariot started in 2014. It was purchased by Ford Motor Company in 2016 for $65 million as part of Ford’s efforts to transform itself from an auto manufacturer into a mobility company. In an increasingly crowded marketplace, Chariot’s 14-seat vans could not successfully compete with cars, public transit, ride-hailing companies such as Uber and Lyft, bike-share and electric scooters.

San Francisco Mayor London Breed is offering Muni bus driver jobs to all of the nearly 300 Bay Area Chariot shuttle drivers.

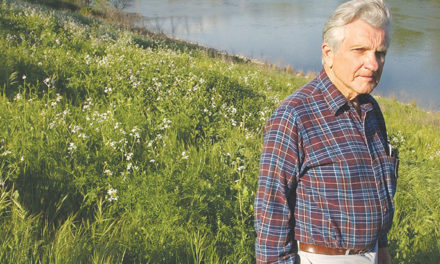

Walt Seifert is executive director of Sacramento Trailnet, an organization devoted to promoting greenways with paved trails. He can be reached at bikeguy@surewest.net.